My Life In Russia’s Service:

Chapter One

CHILDHOOD

The Young Grand Dukes Kirill and Andrei Vladimirovich at Home, painted by Albert Edelfelt (1854-1905), 1881

The Vladimir Villla, Tsarskoe Selo, formerly caller the “Zapadnoe” or Reserve Palace

I was born at Tsarskoe Selo[i] [1] on 13 October[ii] 1876. My father, Grand Duke Vladimir, was the third son of Alexander II.[iii] [2] My mother was the only daughter of the first marriage between Grand Duke Frederick Francis II of Mecklenburg-Schwerin[3] and of Princess Maria Reuss[4]. The line of the Grand Dukes of Mecklenburg-Schwerin is of Slavonic origin[5] and dates from the time when parts of Northern Germany were Slavonic speaking, as some place names still indicate. That is the reason why my mother sometimes used to tell my father that she was more of a Slav then he!

I do not remember my maternal grandparents, my grand-mother having died before I was born and my grandfather when I was quite small.

I was older than my brothers, Boris[6] and Andrey[7], and my sister Helen[iv] [8], as my eldest brother Alexander[9] died a year after my birth.

The house where I was born at Tsarskoe was a bright and very jolly country place built in the late eighteenth-century style of Catherine the Great[10]. It stood in a large garden which had a pond in it. We called it ‘the lake’ as it appeared so very large to us then, and it was my first introduction to water upon which I was to pass so much of my life. On this lake we used to be taken to sail when quite small, and later we rowed on it.

The earliest recollection of my life are the rides in the great park of Tsarskoe on a black pony called ‘Ugoloek,’[v][11]which carried us in a double saddle. I still remember the warm smell of its coat.

The four of us were brought up together and were constant companions throughout our childhood. We lived very closely and intimately and were the best of friends.

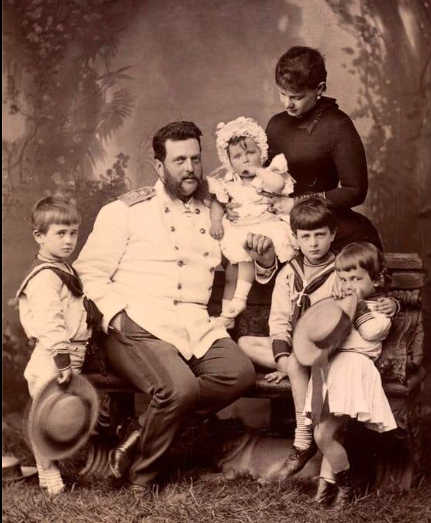

Grand Duke Vladimir and His Family, ca. 1883

My father was a man of strict conservative nineteenth- century principles. None the less, he had exceedingly broad-minded views. His knowledge and memory were fantastic, and surprised those men of learning with whom he came into contact both in Russia and abroad. History was his speciality, and I remember his reading history books dealing with the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to my mother in the evenings while she sat knitting.

He had made a special study of the Court journals which dealt with the daily and hourly records of Russian Emperors and Empresses[12] since, I think, the Empress Elisabeth, but certainly since the Empress Catherine the Great. They were accessible only to members of the Imperial Family, and were not only fascinating reading but of the greatest historical interest.

My father[13] stands out in my memory as an exceedingly kind man, one respected by all for the nobility of his character as well as for his culture and profound erudition. Although gruff in manner and apt to intimidate those who came into contact with him for the first time, yet behind this natural gruffness lay a golden heart.

Later on, he became my dearest friend, and during the decisive moments of life I always turned to him for advice.

All Grandpapa’s[vi] [14]sons were men of parts; the most remarkable of them, in my view, was Uncle Serge[vii] [15], who had the loftiest principles coupled with a character of the rarest nobility. Such he will always remain in my memory.

The friends of our childhood were very carefully chosen, as were the houses which we visited, of which there were not many.

The earliest educational influence to come to us was our English nurse, Miss Millicent Crofts[16], whom we called Milly. She is still alive, and lives, I believe, in Wiltshire. Milly’s near relative was Kitty Strutton, who had been nurse to Father and my uncles Sasha[viii], Serge, and Paul[ix].

When after a long service Miss Strutton retired, she was given a house of her own at Tsarskoe, and when she died, my uncles, including Uncle Sasha and Father, followed her coffin on foot.[17]

This was a singular honour which was rarely bestowed by Russian Emperors, and then only on the highest dignitaries.

Milly was with us from our earliest days, and it was through her that the first language we talked was English. I remember her singing nursery rhymes to us; later she introduced us to the works of English literature, the first of which were Barnaby Rudge and Oliver Twist.

When we left our nursery and were given tutors, Mrs. Saveli was appointed Helen’s governess.

My father was greatly attached to the country and liked to remain at Tsarskoe as long as he could after Christmas, although my parents entertained a great deal during the season in St. Petersburg. In early January we were taken to the Vladimir Palace in the capital, where we remained until late in April, when we returned to Tsarskoe. This was repeated every year.

The Vladimir Palace in a 19th Century postcard

The Vladimir Palace, father’s town house, was a large and sombre place, built in Florentine style, standing on the Neva embankment, and although it was smaller than many other Imperial palaces, it appeared huge to us after Tsarskoe.[18]

Of that period I remember two things: one was its gas-lit passages; interminable they seemed to us and cavernous! Gas at that time was something of a novelty, and even now I remember the interest which it aroused in us. The other memory I have is that of the Carcelle oil lamps, which were wound up like clocks by special lampmen.

It was in our nursery at the Vladimir Palace that I remember several visits from Grandpapa. This must have been two years before his murder.

One occasion especially stands out clearly in my memory of early childhood days in connection with him. He had given us what might best be described as a wooden ‘hill’— a kind of slanting platform from which we used to slide down on a carpet one after the other, like little icebergs sliding down into the sea.[19] Grandpapa on these occasions would stand at the window watching and enjoying our performance with Nurse Milly next to him encouraging us.

I remember, too, the dolls he gave us. They were little stuffed soldiers, dressed in the various uniforms of the Guards. We were Grandpapa’s special favourites.

Of Grandmama[x] [20], I have only one recollection when we were quite small children. She was ailing at the time and we were taken to the famous bedroom in the Winter Palace to kiss her.

Grandpapa was most accessible. He took the keenest interest in everything that went on in his vast empire, and 1 have heard it said that he could often be seen going for walks in the streets of his capital in the early mornings, accompanied only by a large Newfoundland dog[21] of which we were very frightened.

After his murder on 13 March 1881,[xi] [22] members of the Imperial Family were at first closely guarded, but the precautions taken were soon slackened.

It was not until after the revolution of 1905 that it became necessary to take serious measures to protect the life of a Russian monarch. The most exhaustive precautions were then taken to assure the safety of the late Emperor.

Grandpapa’s murder was the first sad tragedy of its kind. There had been palace revolutions, that is true, but as far as the people were concerned, their loyalty to their Emperors was exemplary. The life of their sovereigns was something sacred, and the very thought of an attempt on their lives scarcely suggested itself to them.

When Paul I[xii] [23]was murdered by those who were close to him and owed him their positions and honours, the Russian people, of whose cause he had always been a champion, considered him a martyr, and before the revolution there were pilgrimages to his tomb in the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul. People went there to pray, popular belief invested him with almost a halo of sanctity, and miracles were expected. This was the old-fashioned attitude of Russians to their Emperors, until all this disappeared with the so-called progress and enlightenment.

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna with her three sons, ca. 1879

Mother often told us of the homely ways of Grandpapa, of the tea parties, for example, at which Grandmama presided at the head of the table. These were held in her private apartments and were attended by people of interest, men of letters, scientists, and by important members of Society. Alexey Tolstoi[xiii] [24]was a frequent guest.

All talked freely on those occasions and there was a thoroughly cordial and homely spirit at these gatherings. It was Grandpapa’s habit to visit private houses and balls of those people whom he respected and liked. He was the leader of Society, and all those who came in contact with this kindly and enlightened man were won over to him.

All these cordial relations and this homely spirit between Emperor and subjects and members of the Imperial Family were to disappear completely at a later period.[25]

The only thing which I remember now of the time of his murder are the street lamps shrouded in black for his funeral. I recollect looking through the window of the Vladimir Palace and being impressed by this unusual sight.

It is typical of Grandpapa’s character that what led to his death was his solicitude for a Cossack wounded by the first bomb of his assassin. Quite unconcerned for his own safety, he left his sledge to see whether he could help and to try and comfort the wounded man. This gave his murderer the second chance.

My childhood reminiscences would not be complete without some mention of my recollections of some remarkable figures who played important parts in Russian history. These were my great-uncles, uncles of father, Constantine[xiv][26], Nicholas[xv] [27], and Michael[xvi] [28]. They were the brothers of Grandpapa and sons of Nicholas I. They belonged to that generation and were heroic figures from another age. Quite exceptionally handsome, severe, and exalted men—magnificent types of manhood, they embodied what is best in man in the purity of their character and personal appearance.

Uncle Constantine had been the head of the Navy under Grandpapa. He had also been Viceroy of Poland, but in this capacity, which was a very delicate one, he had not been a success. He was a man of great learning, and, I have heard it said that he wrote his memoirs in Arabic!

He had strong liberal leanings, which made his position none too easy during the period of his activity. He lived at Pavlovsk, which had belonged to Empress Maria Feodorovna, the wife of Paul I. His palace has magnificent parks and woods where we used to ride and drive about at a later period. I remember Uncle Constantine driving up to our skating rink at Tsarskoe. He was paralysed, and we used to run up to his sledge craning our little necks to be kissed by him. I remember his hard fingers and that he smelt of cigars.

We were taken to his funeral service in the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul, the burial place of the Dynasty, where, according to the rites of the Orthodox Church, his body lay in state in an open coffin for the mourners to pay the last respects to the departed. It was the first time that I was brought face to face with death.

I remember, too, our great-aunt, Grand Duchess Constantine—Aunt Sanny, we called her. She was a Princess of Sachsen-Altenburg. [xvii] [29]

We were somewhat frightened of this old lady when we used to be sent to her from our nursery, and I remember distinctly her high-pitched voice, fine white hair, and that she always spoke German to us. I can still see her driving in an open carriage with a kind of awning over it,

which could be opened and closed like an umbrella. I have never seen anything quite the same anywhere else, and think that she was the only person in the world who had such an ingenious cover to her carriage.

Uncle Michael, the other of my great-uncles whom I remember well, was the youngest brother of Grandpapa. He was married to Olga Feodorovna, a Princess of Baden. His only daughter, the Grand Duchess Anastasia, married Mother’s brother, Grand Duke Frederick Francis III of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, whom I used to call Uncle Pitsu. Their children are the present Queen of Denmark, the present Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin[xviii] [30], Cousin Fritzy, and the Crown Princess Cecilia of Prussia, mother of Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia, who married my youngest daughter Kyra this year.[xix] [31]

Uncle Michael had been Viceroy in the Caucasus and in that capacity had brought about that territory’s complete subjugation. He annexed the western portions of that country, and as a result of this campaign he was promoted Field-Marshal in the year 1878.

I remember him distinctly with his great black beard, and the splendid impression he made on us.

These men represented all that was best in a great age of which they were typical, over which the polish and the unsurpassed refinement and culture of the closing years of the eighteenth century had thrown the dying but still brilliant rays of its sunset. And yet these men and their father, Nicholas I, were in their private life very simple and almost ascetic. They slept on camp beds with leather cushions, as Nicholas I had done before them, covering himself with a military cloak. My father resembled his uncles in this and in other respects.

I will never forget the dignity of their bearing and the fine way in which they wore their uniforms. They were Olympians among men—memories of a past age belonging to history.

Those Christmases which we did not spend at Tsarskoe, we passed with Uncle Sasha,[xx][32] Aunt Minnie,[xxi] [33]and our cousins at Gatchina[34]. We went there quite often during the course of the year, but Christmas at Gatchina provided special occasions for family gatherings.

We admired our older cousins and envied them somewhat because they could do things for which we were yet too small.

Misha[xxii] was Uncle Sasha’s special favourite, I too was particularly fond of him because he had a lovable character.

About a week before Christmas Mme Flotov, one of Aunt Minnie’s ladies-in-waiting, used to come to us to inquire what we wanted for Christmas.

Among the things we chose were books, music, interesting clocks, and much else that delighted us. From my childhood up till now I have been very fond of music, and I remember that on one of these occasions I chose the works of Chopin and Tchaikovsky, but that, of course, was later.

Grand Duchess Vladimir and her four children, 1880s

The Christmas tree and the presents were always preceded by a religious service, then, following the traditions of our family, we used to gather in a dark room. Uncle Sasha would then go into the room where the Christmas tree stood to make sure that all was ready. Meanwhile our nerves were on edge with excitement with what awaited us beyond that door. Uncle Sasha would then ring a bell, the door would be flung open, and we would rush into the room of our expectation, preceded by the smallest. The splendid presents were spread upon tables round the Christmas tree.

We were very fond of Uncle Sasha, who was exceedingly kind to us, and many of the happiest hours of my childhood were spent at Gatchina, especially in winter and early spring.

We were often invited there by Cousin Misha[35] to spend week-ends, and in early spring we went rowing on the fine lakes in the park which were fed by cold springs. I remember how very clear the water was. Later we used to ride bicycles along the drives.

During the winter we played all sorts of games in the snow. We skated and tobogganed in the palace grounds down steep banks which, during winter, provided a splendid sliding surface. I remember how we used to slide down these banks in little tubs which were tied one to the other—a whole convoy of them. Down we went one side, along specially prepared runs dug from the snow, and up the other. The incline was steep and the descent was very fast. I used to sit on the knees of a sailor who led this procession.

These occasions provided enormous merriment. Uncle Sasha was often present and would look on, enjoying it all as much as we did.

The palace where he and Aunt Minnie lived had low-ceilinged rooms, and the contrast in their size and low ceilings specially impressed me, as did also the smell of clean wood. Here we gathered before Church when Uncle Sasha used to come in and say: “Minnie, il est temps.” They were in the habit of speaking French together although she spoke fluent Russian.

Another clear recollection which I have of Uncle Sasha of that period is that of his enormous strength. We played a game of our own invention in the grounds of the Anichkov Palace[36]. It consisted of hitting black rubber balls with sticks and then running after them. On such occasions, Uncle Sasha frequently came to join us, and I can see him to this day coming out in his grey toujourka.[xxiii] [37]From the skating rink, using a stout stick with a knob at its end, he made the balls pass clean over the roof of the palace, which was a high building. Only a man of quite exceptional strength could have done this. Then we would run after the ball to recover it.

From early May to early August we used to spend at Tsarskoe and at Krasnoe Selo.

Father was the Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Guard and the St. Petersburg Command, which included the provinces not only within the immediate radius of the capital, but also Finland, Esthonia, Livonia, the province of Pskov, Novgorod, and Archangel. Stretching away as it did to the farthest North it covered a very extensive territory.

The Guard regiments were encamped at Krasnoe from late May into the second half of August, and there were drills and manoeuvres which provided us with many thrills when we joined Father in camp. We lived in little wooden houses allotted to Father, and as we were frequently with the troops, we saw much of military life while we were still children. Mother was an accomplished horsewoman. I remember her galloping among the troops with us trying hard to follow on our little ponies. We looked after them ourselves and rode daily in those summer months. On our return from those rides, a groom would meet us with a plate of carrots and sugar. The ponies, which we drove four in hand, belonged to an Esthonian breed and were reared, I think, on the Baltic islands of Dago and Oesel. The hooves of our mounts and carriage horses were polished with a special mixture of tar to make them black and glossy.

Mother was very popular with the troops, and whenever a cavalry regiment passed her windows they would play those waltzes which they knew she liked. To this day I can hear those tunes.

Mother’s and Aunt Minnie’s names days coincided on August 4,[xxiv] [38]and, on that occasion, we used to go to Peterhof for the fireworks and illuminations.

At Peterhof, I had my first glimpse of the sea, the sea to which I later became apprenticed, which was to become my close companion throughout my life, and which is with me now.

The fireworks were set off from pontoons moored at the sea front in the close proximity of a little castle called ‘Monplaisir.’ We went there when it was dark, in a large brake, drawn by four horses each mounted by a fore-rider dressed in the picturesque liveries of French postillions.

The way to the sea front took us through the large park of Peterhof, to which the public had free access. It was a famous park of its kind with many fountains in it. On these occasions it was lit with many little coloured lamps and looked very attractive. Uncle Paul[xxv] [39] sat in front controlling the brakes, and, as there was no coachman, he directed the fore-riders and was like the captain of a ship. I can still hear his huge voice. “To the left—to the right— stop,” resounded through the great darkening park, as the brake followed the sombre avenues of trees.

We were generally sitting in front enjoying ourselves immensely. It was all very friendly and jolly—a thoroughly warm atmosphere. These are happy memories of youth which were later to disappear completely.

As children we had one valet each—all old soldiers of the Guard. Mother’s servants were mostly drawn from the Naval Guards[xxvi] [40], whilst her maids were Germans. I remember specially Frau Knark and her Hungarian page, Hodura.

Frau Knark was a native of Mecklenburg and had those strange gifts which are found among some country folk in those parts of Europe which have been spared by urbanization, where ancient traditions of the ‘folk’ have succeeded in surviving. Whenever a member of our household had been scalded by boiling water or burnt Frau Knark was called, and by strange and quite inexplicable means in which entirely incomprehensible incantations were muttered by her, she invariably succeeded in curing the scalded skin or the burns and in mitigating the pain.

When we had emerged from our nursery days our first teacher, a Russian, Mlle. Delevskaya, was chosen for us. She came daily, but did not live with us. She was an excellent teacher, a good woman, and very popular. It was she who taught us to read and write Russian. This was done in the old-fashioned way—on slates. We rather teased her, and at times she encouraged our flagging efforts by giving us sweets. This helped considerably in our first studies.

Grand Dukes Kirill, Boris, and Andrei in uniform, ca, 1884

One day Father called Boris, Andrey, and me to him and said: “You are to have a supervisor for your studies; obey him as you obey me.” I must have been about seven or eight then, and we were all very frightened at this announcement.

The supervisor chosen for us was General Alexander Daller[41], a retired and oldish artillery officer.

It fell to his duties to choose tutors for us. Of this he acquitted himself in a somewhat haphazard manner, and some of his choices were far from satisfactory. Among other things he had to supervise our conduct. Each of us had a special conduct book, a sort of log-book for our early navigation on the sea of life.

When Father and Mother were abroad, a thing which often happened due to Mother’s rather delicate health, reports were sent to them by Daller.

Much later on in life when we were grown up, these reports were read to us by Mother. They were most amusing and made us nearly burst with laughter.

One thing, among others, for which I will be always grateful to Daller, is that he taught me to work with my hands. He was a good carpenter, and I took a fancy to this work myself.

In spare hours he read Jules Vernes’ novels to us, then quite new and greatly appreciated.

That period which lies between early childhood and youth, the period of boyhood, is a very important one. Therefore I wish to mention specially those who took a part in my education. They were, with some exceptions, chosen by Daller from the milieu of students and poor officers of the Guard.

First, there was Father Alexander Diernoff[42], our almoner, who remained with us all our lives, and who was instructor in religious subjects till about our eighteenth year. He was our spiritual guide. For him I have nothing but the greatest esteem. He was a man of the profoundest knowledge and of the most exhaustive culture—a well- trained cleric, who taught us Church history, the catechism, and much else belonging to the scope of his authority.

Grand Duke Kirill in his school days, 1880s.

Very unfortunately my early training in mathematics was poor. This was the most important subject which concerned me personally, as I was later to join the Navy. I was not at this stage taught any higher mathematics, trigonometry, mechanics, or dynamics.

History was taught by Vsevolod Chernavin, an officer of the Imperial Family’s own Rifle Regiment, a knowledgeable little man, an excellent teacher, handicapped unfortunately by the manner in which history used to be taught in my youth. More stress was laid on memorizing dates than on the events of importance and the men and women who are the actors in the world drama which history really is. This made this fascinating subject barren and repulsive in the extreme. He only taught Russian history, with a smattering of that of other nations, and no comparative history at all.

The history of other peoples was left to those who were our language masters.

Thus my liking for this important subject was spoilt. Vsevolod Chernavin was an excellent amateur actor, and in this connection I remember distinctly the first time we were taken to the opera. It was Othello. After that Helen’s life was not worth living. We smothered her with pillows—a mock murder—and bullied her rather mercilessly in the way of children, meaning no harm at all. She defended herself splendidly, although there were three of us, all boys, against her. Not very fair play, as generally it is the little girls who bully their brothers. Here, however, she was in a conspicuous minority.

Chernavin’s brother, Vyacheslav, who taught us geography, was christened by Helen—‘ the Kitten,’ for he was a rotund little fellow with black whiskers.

French was taught by M. Fabien d’Orliac, who, I think, died recently. He had three little boys; two of them were twins, who came to play with us.

Mr. Browne was our English teacher. He was a thorough gentleman and very pleasant indeed. He had long white moustaches, and I remember that he was proud of the fact that his name ended with an ‘E.’ We went through the whole of English literature with him, starting with Walter Scott’s novels and Shakespeare’s plays.

Herr Ketzerau, a very typical Teuton, was our German master. He was not attached to the staff of our teachers, but visited us daily. He was an excellent instructor in physical training and fond of out-of-door exercises. From him I acquired a liking for sports—riding, swimming, skating, and golf. I was very fond of gymnastics and a good performer at this. All my life I have been a keen musician, and owe much to Herr Kündiger in that respect. Our first music instructor was most unsatisfactory, and we learnt no music at all with him. He was a German, a Hussar bandmaster, Bode by name.

Herr Kündiger, on the other hand, was excellent, and from him I acquired a fondness for the piano, which I have played all my life.

There was an amateur orchestra in which members of the Imperial Family performed. It had been founded by Uncle Sasha. Uncle Serge[xxvii] played the flute and I the cornet. A Herr Fliege, who was the conductor of the Imperial orchestra, conducted these amateur performances, twice a week in the Grand Duke Michael’s palace. One evening was set aside for string and the other for wind instruments.

In our childhood we suffered from skin trouble owing to the exceptionally hard water at Tsarskoe. The water was so bad that Father had some specially brought from St. Petersburg, where it was taken from the Neva. It was soft and excellent.[43]

To cure us of this complaint we were sent on two occasions to Hapsal, in Esthonia, a delightful watering- place on the Baltic, famous for its curing mud-baths.

Our first visit there was accompanied by an adventure. We went to Hapsal by sea on an ancient paddle steamer, the Olaf, which, not content with its old age, succeeded in running aground in the skerries on a submerged rock, of which there were plenty.

In the end we were towed off by a big battleship, which added considerably to the comic aspect of this episode.

At Hapsal, we lived in a house provided by two very kind old maids, the Countesses Brevern de la Gardie, who sometimes came to visit us. We took a complete staff with us—our servants, cooks, coachmen, and horses.

Hapsal was an excellent place, and we bathed in the sea, went out for drives in the pinewoods, and danced with the girls of the ‘Patriotic Institute’[xxviii] who were on holiday there. There were thirty of them to three of us. We frequently went to concerts, and had a good time.

Our medical attendant was Doctor Hunius, a dear old man, a German Balt, true to his type. He was a great connoisseur of apples and plums, of which he had a great stock in his orchard, and to which we were allowed free access.

In connection with Hapsal, I remember an incident which was as comical as it was dangerous. We had an enormous flagpole near the house in which we lived. An equally large flag had been made for it, which was hoisted by us every morning. One day we decided to hoist Helen instead of the flag. She was a willing party to this conspiracy. Accordingly we tied the flag-rope round her and began hoisting her up. A sailor had become suspicious of our proceedings, but could not see clearly what was going on, as the foot of the pole stood amongst some bushes which hid us from view. But when he saw a human parcel, in the shape of a small girl, proceeding slowly up the pole, he ran up to us and arrived just in time, as Helen was by then merrily swinging in the breeze about thirty- five feet up from the ground. Needless to say, the incident closed with a well-deserved dressing down.

During our second visit to Hapsal—also in the ’eighties— mother was very ill, and she very nearly died. We were not told anything about it at the time.

Suddenly, one night, we were rushed off to Peterhof, and in order to catch the train there we had first to go to Reval, the nearest station. This was a matter of about one hundred kilometres, or about sixty-two miles, and had to be covered during the night as the train was due to leave Reval early in the morning. Doctor Hunius provided us with a huge amount of apples, and off we went into the night in a carriage drawn by six horses mounted by outriders. We arrived in time to catch the train, to which an Imperial carriage had been added for us. At Peterhof, we met Aunt Marie, the Duchess of Edinburgh, my father’s only sister. She was to become my future mother-in-law, and was, during that critical period, staying with my mother.

I remember that to keep us quiet she frequently took us for drives. Through her we got to know many places which we had not seen previously. She knew the place excellently. I remember that she would sometimes stop the Imperial carriage in which we drove to buy fruit from pedlars at the wayside. With us she was strict and allowed no fooling, but had an exceedingly kind heart.

Nearly every second or third autumn, when father was off duty after the camp at Krasnoe, we went to stay with Uncle Friedrich, Aunt Anastasia, and our cousins[xxix] at Schwerin. We loved these visits, and were on the friendliest terms with our relatives. The old Crown Princess of Prussia, the sister of William I, the Grand Duchess Alexandrine of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, we called her Grandmamma, lived in a little schloss at Schwerin. She was always charming to us, speaking the very perfect and exquisite French of the eighteenth century. They had all been brought up according to the best traditions. She was the daughter of King Frederick William III of Prussia and of his famous and beautiful wife, Queen Luise, a Princess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Frederick William IV of Prussia and Queen Luise had two other children, one of which was the Emperor William I and the other the Empress Alexandra Fedorovna, wife of the Emperor Nicholas I. On one occasion she gave us a dinner, and although we were small children and she was over eighty years of age and paralysed, she had herself rolled into our dining-room in her chair to be with us during this dinner. In spite of our youth, she had put on full evening dress with her decorations, and wore the Romanoff Family Order[44], and, according to the old traditions, she carried a fan in her hand. I will never forget this outstanding example of old-world discipline and supreme refinement that belongs to another age.

Grandmamma’s son was my maternal grandfather, the Grand Duke Frederick Francis II of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. I remember the very striking and beautiful family seat of the Grand Dukes of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Surrounded as it is by a great lake it is one of Germany’s famous historical castles and has, moreover, the reputation of being haunted. It was here that we used to stay during our frequent visits to our relations.

The seat of the Dukes of Mecklenburg Schwerin, Mecklenburg, in a 19th c. postcard

It is a magnificent and imposing edifice, and stands in the great lake of Schwerin. On one of these visits, I and my brother Boris were lodged in the two towers which flanked the great entrance gate to the courtyard of the castle, so that I occupied a room in one of the towers and he slept in the other. This occasion coincided with the death of Uncle Pitsu.[xxx]

The rooms in which we were lodged were cavernous and circular, and what struck us as odd and uncanny were the many doors which were always kept locked and led ‘goodness knows’ where. As we were children, and were afraid of sleeping alone in those gloomy rooms, it was decided that we should sleep together in one of those towers. Uncle Pitsu’s body was at the time lying in state in the chapel of the castle.

One night, while Uncle’s body was still in the chapel, we heard quite distinctly the clatter of the hooves of galloping horses entering the courtyard, and then, after a while, the sound of more horses and the rattling of a carriage as its iron-ringed wheels heavily bumped on the cobbles of the yard. Then there was silence, but only for a brief spell. Then we again heard the galloping horses and the sound of a carriage passing the towers through the gate. For the moment, and having no other explanation, we thought that this unusual din was caused by the changing of the guard which used to be posted at the gate of the castle.

Later we told our experience to Mother, from whom we heard that, according to an ancient tradition, there was a story current among the members of her family that whenever a Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin passed away the carriage of death was supposed to come for the spirit of the departed Grand Duke to fetch him away from his castle, but neither she nor any of her family had seen or heard it.

This was only one of the many uncanny things that went on in this awe-inspiring place. There was, for example, the story of a dwarf of the sixteenth century, who, at one time, had been a Court jester, and who was supposed to be haunting certain rooms of the castle. One of the Grand Dukes had sought to appease that restless spirit by erecting a monument to him in the castle grounds. I know not whether this device succeeded in preventing the ghost from his nocturnal wanderings.

Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich, 1880s (Levitsky)

We used to go out rowing on that large lake with our tutor and a boatman, who, I remember, wore a peculiar blue livery. On one occasion we were surprised by a squall and ended very nearly in disaster. We were too small to row well, and one of us had to do the steering, of which he did not acquit himself well, so that the brunt of the work fell on the tutor and the boatman. We rowed for life and began to ship water. In the end, however, we reached land safely, but only just in time.

Father liked these visits particularly, as he was a keen shot, and for this the forests of Schwerin were ideal, especially for stags. Later I, too, shot there once or twice. These visits to Schwerin are among my most pleasant recollections of that period.

I think that my earliest memory of a journey abroad was a visit to Switzerland. Mother’s health required frequent visits abroad, and this particular one, I believe, was to Vevey. I recollect little of it now except that I was told that people stopped in the streets and remarked to my attendant: “What a pretty little boy.” According to the fashion of that time I wore a little frock with ribbons.

Another very dim recollection is a visit to Biarritz. The only thing which I remember about it now is that I made little sand-pies in a tent[45].

About the same period in the early ’eighties I have my earliest recollections of Paris. We stayed at the Hotel Continental[46], which, I believe, still exists. I remember distinctly the horse-drawn buses in the rue de Rivoli, the grey horses which drew them, the clatter of their hooves on the wooden pavements and the cracking of their drivers’ whips, as well as the smell of fresh asphalt.

In the late ’eighties and in 1891, when I was about twelve or thirteen, we went to St. Sebastian in Spain. There we met Queen Christina of Spain, who was a Hapsburg by birth. I remember well her pretty gait and her elegant and truly queenly bearing. She was there with her children, Alfonso XIII and his sisters, Mercedes and Maria Theresia. The King was a rather naughty little boy, always running away from his nurse and scampering about all over the beach.

We bathed in the sea, my first introduction to the Atlantic Ocean, and Queen Christina offered us the use of her bathing machine. This had several rooms and stood on rails. It could be adjusted to the state of the tides by being pulled up and down by a steam winch from the land. She gave us some delicious, dark, sweet Spanish wine, Malaga, in little glasses.

Many well-known people came to St. Sebastian, and the Grand Duke Alexander Michaelovitch was one of them.

We often went for drives inland to visit places of interest like Tolosa and the famous monastery of Loyola.

Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich, ca. 1888 (Bergamasco)

Sometimes we went over factories. I remember two of them especially—one was a biscuit factory and the other manufactured the famous Basque berets in all the colours of the rainbow.

Queen Christina had a famous historical castle not far from St. Sebastian, where she lived simply in the entourage of a very amiable Spanish Court.

She was a remarkable woman, and we admired her very much.

Our visit to Spain was suddenly interrupted by the death of Aunt Alice[xxxi] [47], Grand Duchess Paul, who died in giving birth to my cousin, the Grand Duke Dimitry, in the year 1891. Father and Mother had to leave hurriedly to return to Russia.

The last reminiscence of a journey abroad in my childhood was one to Finland, a Grand Duchy, and not, properly speaking, a part of the Russian Empire, but under the suzerainty of the Crown. We went to see the famous rapids of Imatra and Walinkosky, truly magnificent examples of the force and beauty of nature. There was good trout fishing in that region on the property of General Astasheff. It was the custom there to weigh and measure every trout caught and to record the result on the stone quays of the Saima Canal.

During my childhood I had never been taken to visit the interior of Russia, but that was to come later.

Footnotes

(2024)

[1] The Grand Duke was born in the Vladimir Villa at Tsarskoe Selo 30 September 1876 (OS). Originally built between 1816 and 1824 as a small palace for the Kotchoubey family, the building had been acquired by the Imperial family in 1858 as a “Reserve” or guest palace. It was granted by Alexander II to his son in 1875, and after Grand Duke Vladimir’s death in 1910, Nicholas II declared it would be forever known as the “Vladimir Palace.”

[2] Emperor Alexander II Nikolaevich, born eigned 1855-1881.

[3] Grand Duke Frederick Franz II of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, 28 February 1823 – 15 April 1883. Reigned 7 March 1842 until 15 April 1883.

[4] Princess Maria Auguste Mathilde Wilhelmine Reuss zu Köstritz, 26 May 1822 – 3 March 1862. After her marriage at Ludwigslust on 3 November 1849, she became Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

[5] The House of Meecklenburg are descendants of one Prince Pribislav, an Obotrite (Slavic) prince. Pribislav converted to Christianity and accepted subjecture to the Saxon Duke Henry the Lion (r. 1142–1180), and became known as “Lord of Mecklenburg” The name was derived from ‘Mikla Burg’ [Large fortress] their main residence.

[6] Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich of Russia, b. St. Petersburg 24 November 1877 – d. Paris 9 November 1943

[7] Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich of Russia, b. Tsarskoe Selo 14 May 1879 – d. Paris 30 October 1956

[8] Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia, b. St. Petersburg 17 January 1882 – d. Athens 13 March 1957, later Princess Nicholas of Greece and Denmark (m. Tsarskoe Selo 29 August 1902

[9] Grand Duke Alexander Vladimirovich of Russia, b. 31 August 1875 – d. 16 March 1877.

[10] The “Vladimir Villa” or “Vladimir Palace” (now at Sadovaya Ul. 22; Tsarskoye Selo) was constructed for the Kotchoubey family between 1817-1824 by the architect Stasov on land granted to them by Alexander I in 1816. In 1835 the house and gardens were acquired by the Ministry of the Imperial Court and Estates, and from 1858 on the house served as a “reserve” or guest palace. In 1875, the “reserve” palace was given to Grand Duke Vladimir as a wedding present, and on 27 September 1910, Nicholas II changed the name of the building to the “Vladimir Palace.” The palace was confiscated after the revolution, and housed several organizations. During World War II, the palace was severely damaged, and only the walls survived. In the 1950s, the palace was reconstructed and became the “Pushkin House of Pioneers” and later, home to the First Border Cadet Corps of the FSB of Russia. On 24 June 2010, as part of the celebration of the 300th anniversary of Tsarskoye Selo, the building has served as “Wedding Palace No. 3.”

[11] “Ember”

[12] Kammer-Fur’ierskii Tseremonialnyi Zhurnaly, or, Chamberlains’ Ceremonial Journals (published between 1695-1918) are the published historical collections of the daily notes kept at the Russian court by appointed courtiers known as “Chamber Fouriers .“ The beginning of the journals was laid by Peter I in 1695, who began to keep a diary called "Journal or Day Notes", reflecting the course of hostilities in the Azov campaign. By the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna, journals had become daily reconstructions of the everyday life of the imperial family and their interactions with persons close to the court, and as Grand Duke Kirill notes, by the reign of Catherine II, they were formerly printed in editions no larger than 200 copies annually, and access was limited to the members of the Imperial family and palace staff.

[13] H.I.H. Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia, b. Winter Palace, 22 April 1847 – d. 17 February 1909. The third son of Emperor Alexander II followed a military career and occupied important positions during the last three reigns. Educated and highly cultured, he was appointed President of the Academy of Fine Arts., and served as a sponsor of the Imperial ballet. He became an Adjutant-General in 1865, Senator in 1868, and a member of the Council of State in 1872. Under Alexander III, he served as a member of the Council of Ministers, Commander of the Imperial Guards Corps, and finally as Military Governor of Saint Petersburg.

[14] Emperor Alexander II the Tsar-Liberator, b. 29 April 1818 – d. 13 March 1881, reigned from 1855 until his assassination in 1881.

[15] Grand Duke Serge Alexandrovich of Russia, b. 11 May 1857 – d. 17 February 1905. Sergei Alexandrovich was born the fifth son and seventh child of Emperor Alexander II of Russia, and married Elizabeth of Hesse and the Rhine in 1884. Served as Governor-General of Moscow from 1896 until 1905. He was assassinated by terrorists one month later.

[16] Millicent Crofts, b. 1851 – d. 1941.

[17] Katherine “Kitty” Strutton, b. 1854 – d. 1894. “Miss Strutton… died in the Winter Palace at St. Petersburg. Miss Strutton, who was an English woman, loved Alexander Romanoff as dearly as though he had been her son. The Emperor and his two brothers attended the funeral, following the hearse on foot from the palace to the 'English cemetery’, almost two miles apart. His Majesty and the two Grand Dukes had carried the coffin from the death room to the hearse. When the body was lowered into the grave, the Czar, it is said, wept like a child.” (Indianapolis Journal, Indianapolis, Marion County, 10 November 1894, p. 4.)

[18] The Vladimir Palace (Dvortsovaya Naberezhnaya, 26) was designed and reworked by some of Russia’s greatest architects, and remains one of the few relatively intact Romanov period interiors. Vasily Kenel, Aleksandr Rezanov, Andrei Huhn, Ieronim Kitner, Vladimir Shreter and Maximilian Messmacher all executed sections of the complex. Construction work on the waterfront lasted from 1867 to 1872,and additional construction and extensions continued peripatetically throughout the 19th and early 20th century. Since the 1920’s, the palace has served as the House of Scientists, a semi-private club.

[19] Other “Russian Hills” or slides of this type were located in the Winter Palace, the Alexander Palace, and at Gatchina Palace.

[20] Empress Maria Alexandrovna of Russia, born Princess of Hesse-Darmstadt b. 8 August 1924 – 3 June 1880

[21] “Mulya” -- Alexander II had a number of dogs, of whom the mutt “Milord” was perhaps the most famous. Other dogs are mentioned however, in particular his large Newfoundland, called “Mulya”. Tyutcheva reports that once, at a concert, Mulya sauntered up to the violinist and put her front paws on his shoulders. The musician continued to play, and the dog moved her muzzle back and forth behind the bow. The tsar asked: “Venyavsky, is the dog bothering you? “Your Imperial Majesty,” cried the exhausted artist from behind the dog, “I’m afraid it is I who am disturbing her!”

[22] Alexander II was assassinated by the second of three bombs brought by Narodnaya Volya terrorists Nikolai Rysakov, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, and Ivan Emelyanov on 1/13 March 1881.

[23] Emperor Paul I Petrovich, b. 1 October 1754 – d. 23 March 1801. The Emperor Paul was assassinated by a group of close friends, including Count Peter von der Pahlen and Count Nikita Panin, among others.

[24] Count Alexey Konstantinovich Tolstoy (5 September 1845 – d. 10 October 1875) known as A.K. Tolstoy was an important 19thcentury Russian Historical dramatist, poet, novelist, and satirist. His mother, Anna Perovskaya was an illegitimate daughter of Count Alexey Razumovsky, and as a result, had very close connections at court. Tolstoy was a childhood friend of Alexander II, and close to his entire immediate family. He was a second cousin of the author Count Leo Tolstoy.

[25] Here, Kirill Vladimirovich alludes to the later influences of the Empresses Maria Feodorovna and Alexandra Feodorovna on greater Romanov family life.

[26] Grand Duke Constantine Nikolaevich of Russia, b. 1827 – d. 1892. Grand Duke Constantine was was born the second son of Nicholas I and Alexandra Feodorovna, and served as Viceroy of Poland from 1862-1863.

[27] Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich of Russia, b. 1831 – d. 1891. Grand Duke Nikolai was as the third son and sixth child of Tsar Nicholas I and Alexandra Feodorovna. Also referred to as Nicholas Nikolaevich “the Elder “ to distinguish him from his son, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia (b. 1856 – d. 1929). A known military authority, as Field Marshal he commanded the Russian army of the Danube in the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878.

[28] Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich of Russia, b. 1832 – d. 1909. Grand Duke Michael was as the fourth son and seventh child of Emperor Nicholas I and Alexandra Feodorovna. He served 20 years (1862–1882) as the Governor General of the Cucasus in Tbilisi. During the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878), was appointed Field Marshal General in April 1878.

[29] Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna of Russia, b. 1830 – d. 1911. Born Princess Alexandra of Saxe-Altenburg, she was the fifth daughter of Joseph, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg and Duchess Amelia of Württemberg. Through her six children, who married into the royal houses of Greece and Württemberg she is an ancestress of every reigning European royal house.

[30] “Cousin Fritzy” Friedrich Franz, Hereditary Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin b. 1910 – d. 2001. The eldest child of the reigning Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Frederick Francis IV, and his wife Princess Alexandra of Hanover. His father abdicated on 14 November 1918, and he did not succeed to the throne. Childless, he was passed over in favor of his younger brother Duke Christian Louis In May of 1943, when a family council was called by the Grand Ducal family and it was decided that the family headship and property would pass to the junior branch.

[31] Grand Duchess Kira Kirillovna of Russia, b. 1909 – d. 1969. The second child of Grand Duke Kirill and Grand Duchess Victoria, HH Princess Kira Kirillovna was born in Paris in 1909, after Emperor Nicholas II had recognized her parents’ marriage and restored the succession rights of their children. Raised in Germany and France, she was elevated to the rank of Grand Duchess on her father’s accession to headship of the house in 1924. She married Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia, heir to the German and Prussian thrones, in 1938.

[32] “Uncle Sasha” Emperor Alexander III of Russia, b. 1845 – d. 1894. The second son and third child of Alexander II and Empress Maria Alexandrovna, Alexander Nikolaevich was raised for a military career and was not expected to take the throne. On the sudden death of his elder brother Nicholas, Alexander married his brother’s fiancée, and took the throne in 1881. Rejecting the liberal reforms of his father, Alexander, known as “the Peacemaker” presided over an autocratic period in which no wars were fought, but where censorship and intermittent civil violence was the rule.

[33] “Aunt Minnie” Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia, b. 1847 – d. 1928. Born Princess Marie Sophie Frederikke Dagmar of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, she was the fourth child and second daughter of Prince Christian and his wife, Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel. In 1852 Prince Christian became heir-presumptive to the throne of Denmark, largely due to the succession rights of his wife Louise as niece of King Christian VIII. In 1853, he was given the title Prince of Denmark, and his daughter became known as Princess Dagmar. In 1864 she became engaged to the Russian Tsesarevich Nicholas, and moved to Russia. Nicholas died in April 1965, and instead, Minnie married Nicholas’ younger brother who became Alexander III. The marriage was a success, and as Empress Maria Feodorovna, Minnie became matriarch of the entire House of Romanov, leaving Russia in 1917, and dying in 1928.

[34] Gatchina Palace, designed by Antonio Rinaldi (Italian, b. 1709 – d. 1794) was built between 1766-1781 for Paul I. It was the favorite residence of Alexander III and his family.

[35] “Cousin Misha” Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia, b. 1878 – d. 1918. The youngest son of Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna, the quiet “Misha” had an unremarkable path in life until his illegal marriage in 1912 to a twice-divorced commoner caused his exile from Russia. He was allowed to return with his wife and son in 1914 during WWI and fought with distinction in the “Savage” Regiment. In 1917, he joined his Uncle, Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich and his cousin, Grand Duke Kirill, in a plot to keep Nicholas II on the throne through issuing concessions, but the Manifesto of the rand Dukes was a failure. Named heir to the throne after Nicholas II removed his son from the succession, Michael issued a conditional acceptance of the throne, was exiled by the Bolshevik Government, and was the first Romanov to be murdered in July 1918.

[36] The Anichkov Palace, at Nevsky Prospect, 39, takes its name from the neaby Anichkov Bridge. Though its authorship is in question, (sections of the design have been attributed to Zemtsov, Rastrelli, Quarenghi and others) the palace served as the home of Tsesarevich Alexander and Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna. After the death of Alexander III, leaving the Winter Palace to her son and daughter in law, Empress Maria Feododovna made it her primary residence.

[37] The “everyday” (From the French toujours) tunic of the Russian military.

[38] The Feast Day of St. Mary Magdalene, Equal-to-the-Apostles on July 22 (old Style) August 4 (new Style).

[39] “Uncle Paul” Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia, b. 1860 – d. 1919. Grand Duke Paulwas the sixth son and youngest child of Emperor Alexander II of Russia by his first wife, Empress Maria Alexandrovna. Destined for a military career, Paul Alexandrovich joined Russian Army where he served in the Cavalry and as an Adjutant-general to his brother Emperor Alexander III. In 1889, he married Princess Alexandra of Greece, with whom he had two children. After his wife’s death, he married without the emperor’s permission, was exiled, and had a second family in France. After 1909, he enjoyed prestige as the only surviving son of Alexander II, and In 1912, he was allowed to return to Russia with his wife, Princess Paley, and their children.

[40] Gvardeiskii Ekipazh, Garde-Equipage, or ‘the Naval Guards’ were formed on 16 February, 1710 by Peter the Great. By 1810, the regiment had been defined as a group of elite sailors assigned to special escort ships, the Imperial yachts, and to Court and garrison guard duty. They were the cream of the officer class of the Russian Imperial Navy, and hand-selected for service due to their breeding and expertise. The Naval Guards were composed of a non-combat team, a musical choir (orchestra) and an artillery team with a total number of 434 men. By 1917, there were 4400 members. Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich was enrolled in the Guards on 14 May 1896, and was made last Commander of the Guards by Nicholas II on 16 March, 1915.

[41] General Alexander Alexandrovich Daller, b. 1839 – d. ?) General Daller was educated at the Mikhailovsky Artillery School and Was graduated from the Mikhailovsky Military Academy. He served on staff as a Military Agent in Berlin from 1871-1884, and then joined the staff of the Directorate of the Artillery. Promoted to Lieutenant-General in 1894, he became a tutor to Grand Dukes Kirill, Boris and Andrei.

[42] Protopresbyter Alexander Alexandrovich Dernov, b. 1857 – d. 1923. Born in Vyatka Province, Fr. Alexander was ordained a deacon and priest in 1882, declared Archpriest in 1899, and created a Protopresbyter in 1915. In 1884, having impressed Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, he was invited to teach the Zakon Bozhii [Law of God] to the Grand Duke’s children, and in 1888 he became a rector at the Court Church of the Peter and Paul Cathedral. In 1915, he became the head of the Court Clergy at the Winter Palace. In 1918 when the Imperial Churches were closed, he became directly subordinate to Patriarch (later Saint) Tikhon. In 1922 he was arrested for “resistance to seizure of church valuables” and was taken to Shpalernaya prison, where he died in 1923. He is considered one of the New-Martyrs of Russia. (Archive of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation for St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region; D. P-89305)

[43] This incident is seriously underplayed by the Grand Duke. The water beneath the Vladimir’s villa came from a well which was tainted by wastewater from the palace complex itself, causing enormous trouble in the early days of the family’s residence there. This situation involved not just water “brought from St Petersburg” but a new freshwater system, installed between 1879-1885 under the supervision of A.F. Vidov.

[44] “Romanoff Family Order” In this case, Grand Duke Kirill appears to mean the Order of St. Catherine, 1st Class, which was awarded on 1 July 1817 to the Grand Duchess Alexandrine. As sister of the future Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, she received the order shortly after her sister’s marriage to Tsesarevich and Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich on 13 June, 1817. The Order of St Catherine was only awarded to women of the Imperial House, foreign Royal women, and ladies of the highest nobility.

[45] “Biarritz” While the memories of Grand Duke Kirill of the Spanish resort are few, the influence of the Russian community’s love of the town made famous by the Empress Eugenie of the French remains. The Orthodox Church of St. Alexander Nevsky was begun in October 1890, according to plans of N.N. Nikonov. The church was consecrated two years later, and completed in 1899.

[46] “Hotel Continental” Today the Westin Vendome, 3 rue Castiglione. Built in 1876-1878 by Charles Garnier’s son-in-law Henri Blondel, the hotel had the reputation of being the most luxurious in Paris, and served as a home away from home for many of the Russian Grand Dukes including the Vladimirs until the opening of the Ritz in 1898. Several of the main reception rooms retain their appearance from the time of the Vladimirs.

[47] “Aunt Alice” Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark, b. 1870 – d. 1891. The eldest daughter of King George I of the Hellenes and his wife Queen Olga (born Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna), she married her cousin Grand Duke Paul in 1889. Much beloved, she died due to complications to her second pregnancy with Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich.

Historical Footnotes

(1939)

[i] One of the residences of Russian Emperors and of members of the Imperial Family near St. Petersburg. Famous for its exquisite architecture and splendid parks.

[ii] 30 September, old style.

[iii] Alexander II reigned 1855-1881. He married Princess Marie of Hesse-Darmstadt. He was the eldest son of Nicholas I and of Princess Alexandra of Prussia.

[iv] Wife of late Prince Nicholas of Greece. Her children are Marina, Duchess of Kent, Princess Olga of Yugoslavia, and Countess Elisabeth Toerring.

[v] Little burning lump of coal.

[vi] Alexander II.

[vii] Grand Duke Sergey Alexandrovitch, Governor of Moscow, assassinated in 1905. His wife was Grand Duchess Elizabeth, Princess of Hesse, sister of the late Empress Alexandra.

[viii] Alexander III reigned 1881-1894.

[ix] Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovitch, married Princess Alexandra of Greece. Their children are : Grand Duke Dimitry and Grand Duchess Marie.

[x] Empress Marie Alexandrovna, who before her marriage was Princess Marie of Hesse-Darmstadt, 1824-1880.

[xi] 1 March, new style. [Ed. Note: 1 March is the old style date.]

[xii] Paul I, reigned 1796-1801.

[xiii] Russian poet and man of letters, distant relative of Count Leo Tolstoi.

[xiv] Grand Duke Constantine Nikolaevich, 1827-1892.

[xv] Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, the elder, 1831-1891.

[xvi] Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich, 1832-1909.

[xvii] Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna.

[xviii] Grand Duke Frederick Francis IV.

[xix] 1938.

[xx] Emperor Alexander III.

[xxi] Empress Maria Feodorovna, wife of Alexander III.

[xxii] Grand Duke Michael, youngest son of Alexander III.

[xxiii] Everyday military tunic from the French toujours, always.

[xxiv] July 22, old style.

[xxv] Married Princess Alexandra of Greece ; his children are Grand Duchess Marie and Grand Duke Dimitry.

[xxvi] 'Gwardeyskiy equipage' in Russian. There is no equivalent to this in the Royal Navy. They were not Marines, but contingents of sailors belonging to the Imperial Guards and allotted to special escort ships and the Imperial yachts. They were the pick of officers and men of the Russian Imperial Navy. At the time of the war the cruiser Oleg, the flotilla-leaders Voiskovoi and Ukraina, and the several yachts were manned by the Guards. They wore a distinctive uniform.

[xxvii] Grand Duke Sergey Alexandrovich

[xxviii] A High School for girls, usually orphans.

[xxix] See supra.

[xxx] Grand Duke Frederick Francis Ill of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

[xxxi] Prince Alexandra of Greece, wife of Grand Duke Paul, brother of Alexander III.