My Live in Russia’s Service:

Chapter Six

war and marriage

I spent a few very quiet weeks with my parents and then with Boris at Tsarskoe.

Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich’s “English” Villa at Tsarskoe Selo, ca. 1900

My brother had had an English country-house built for him there by Maple and Company and kept an English butler and an English coachman, both of them very true to type.

During this period, I had an interview with the Emperor, who did not, however, give me any clear indication as to the future prospects of Ducky and myself, beyond that there was some hope that things would, possibly, straighten out. He was very affable and showed much sympathy.

I obtained his and Father’s consent to pay a visit to Coburg[1]. I may mention here that no member of the Imperial family, unless in the service of his country, was allowed to leave Russia without obtaining the Emperor’s permission to do so. This was a well-established rule, which applied to State functionaries as well.[2]

The rest of the summer I spent at Castle Rosenau, near Coburg, where Aunt Marie, Ducky, and Cousin Beatrice were at the time.[3]

Ducky and I enjoyed our freedom and made plans for the future. The making of such plans is one of the consoling things of life, because they are based on hope, and although they may never mature the very making of them is a pleasant pastime. We rode and drove much in the forests near the castle and motored a great deal. I had two cars with me—the small one which I have mentioned already and a large six-seater touring-car which resembled a clumsy kind of omnibus. It had six cylinders, but was far less efficient than the other, breaking down with an enervating regularity. It was equipped with a silver service for picnicking.

Motoring in those pioneering days was accompanied by continuous trouble either from frequent breakdowns or from people and animals which one met on the way. Besides, cars in those days were the ‘rich man’s pleasure’ and anyone having a car was naturally marked down as a capitalist, and therefore as an enemy of the people. I often met with some who manifested their outraged feelings in various ways of indignant behaviour as I passed by them. Apart from offending people politically there was another side to the unpopularity of motor cars, one, indeed, which had a more reasonable cause. They terrified human beings and all manner of beasts. Chickens were scattered in all directions, dogs run over, horses shied, upsetting carts into ditches. There were claims for damage done; road tolls had to be paid. Frequently one was stopped by the police and things had to be explained. In my exasperation I had the number plate replaced by a crown and fixed a special flag on the bonnet which made things easier.

In spite of such episodes, we enjoyed our trips immensely. We went through the length and breadth of the lovely Thuringian Forest, visited Nuremberg, Bamberg, Gotha, and much else of what is old and fascinating in that part of Germany which I had not seen before. We picnicked together out in the open, in nature’s solitude and far from the busy world. Life was full and inviting. There was hope and the joy of living which comes to one on such occasions with the whole vigour and entirely carefree spirit of youth. It was an appeasement after much anxiety and sorrow.

In the autumn of 1903 I paid a visit to Palermo for my health, and on my way to Russia spent Christmas at Coburg.[4]

It was a thoroughly international Christmas, and the manner of keeping this feast was as effective as it was a well-matched combination of the best features of the English, German, and Russian way of celebrating it.

During the course of this very jolly period, the storm which had been gathering ominously for some time over Asia had reached the climax of its pent-up force. Silently, and imperceptible save to those who knew, it had spread until it suddenly broke over an unsuspecting Russia with all the shocking violence of surprise.

On the night of 9 February 1904[i] the Japanese, without declaring war on us, had attacked three of the best units of our fleet while these were lying in the outer roads of Port Arthur. The Pallada, Retvisan, and Tzarevitch were badly damaged by enemy torpedoes and put out of action for the time being.

On 10 February[ii] the Variag and Korjeetz were destroyed at Tchemulpo and at the same time, two days only after the commencement of hostilities, the Boyarin and Yenissei were sunk by our own mines. Two days of war had cost us seven ships.

Baron Rosen on page 235 of Forty Years of Diplomacy, from which I have quoted previously and which I recommend to those who are interested in the events which led up to the Russo-Japanese War, speaks thus of the fight between the Variag and Korjeetz and the Japanese squadron.

‘Real feeling was shown by the foreign sailors who witnessed the tragic destruction of our two small vessels by a powerful Japanese squadron in the harbour of Chemulpho on 8 February 1904. Officers of the French cruiser Pascal, which brought to Shanghai part of the survivors of the battle, related to me with profound emotion how the Variag, followed by the gunboat Korjeetz, having accepted the challenge, slowly steamed, colours flying, officers and men on parade, past the foreign men-of-war anchored in the roads, saluted by our national anthem, heroically going to meet certain destruction at the hands of the enemy who had spread the numerous and powerful vessels of his squadron in a wide semicircle, rendering escape a matter of utter impossibility.’

I was a naval officer and as such had no intimate knowledge of the real story of the drama that had so suddenly unfolded itself. There is nothing I personally know which I can add to the history of this war. As I have already said, I was taken by surprise. Not, indeed, that I had not suspected the possibility of war—that was always likely, due to the conflict of ambitions in the Far East—but the tragedy was overwhelming in its suddenness.

I will, therefore, quote from Baron Rosen’s book, who, in his capacity of our then Ambassador to Tokyo, is in a unique position for giving a clear and absolutely authentic account of the events which led up to that war.

First, however, I may mention that Japan considered Korea as her sphere of influence in the same way as we looked upon Manchuria as our field of action.

Baron Roman Romanovich Rosen (1847-1921)

I have already mentioned that we were embarking on an extensive East Asiatic policy. Japan, too, was pursuing such a plan. The plane upon which the two opposing currents came into contact and produced the spark which caused the conflagration was Korea. Great historical events are more often than not caused by petty incidents. The incident in this case was a timber concession in the region of the Yalu River in Korea. This concession had been granted by the Korean Government to a Russian company, and this is what Baron Rosen says concerning it on page 211 of his book: ‘It appears that he (M. Bezobrazoff) had submitted to the Emperor a grandiose plan of the acquisition for Russia in the Far East of an Empire similar to Great Britain’s Indian Empire by a similar process of gradual expansion, begun and effected by an organization framed on the lines of the defunct East India Company. The timber concession on the Yalu obtained several years before that from the Korean Government, by a merchant from Vladivostok, was to have served, so to speak, as an entering wedge.’ On page 213 he continues: ‘They seemed to have obtained, under a pretext of needed protection, the dispatch to the Yalu of a considerable body of troops who had begun the construction of earthworks which looked very much like future batteries.—Now the absurdity’ (p. 214) ‘of a power like Russia, possessing on its own territory in Europe and Asia an almost untouched forest area of more than two million square miles, needing a timber concession at the far away mouth of the Yalu River on the Korean-Manchurian frontier—defended by earthworks and Cossacks—was too self-evident not to give rise in the minds of the Japanese to the unshakable conviction that we were preparing for some armed aggression against the Japanese interests in Korea. All these provocative proceedings were welcome to the large and influential party which was in favour of bringing the chronic conflict with Russia to a decisive issue by force of arms.’

Vyacheslav von Plehve before 1903

Of Plehwe, our then Minister for Foreign Affairs, Baron Rosen says: ‘As a very intelligent man, he could not have failed to realize that our whole Far Eastern policy, of which the Yalu enterprise was one of the most disquieting features, was bound to land us in the end in an armed conflict with Japan.’ And on page 219: ‘In Japan, however, everything seemed perfectly calm, at least on the surface, until two events occurred in Russia which produced in Japan an impression reflected in a remarkably alarmist undertone, perceptible in the utterances of the Press. These events were: the fall from power of Witte,[iii] and the creation of a Viceroyalty of the Far Fast with Admiral Alexeeff as Viceroy.’ And then—on page 222: ‘Their immediate aims’ (i.e. the Japanese) ‘were the ousting of Russia from Korea and, if possible, from Manchuria as well, and the establishment of a Japanese protectorate over Korea, leaving to the developments of the future all ultimate aims such as the final annexation of Korea, the gradual absorption of Manchuria, and other ambitious plans in regard to China.’ On page 226 he continues: ‘I told the Viceroy frankly that as far as I could judge the Japanese Government were determined to secure the exclusive control of Korea by negotiation, if possible, if not, then by force of arms; that they were sure of moral support of the Western powers for whose benefit they were pretending that they were defending the independence and integrity of Korea and China against Russian aggression ; that we could not possibly hope to retain our position in Korea as well as in Manchuria; that in my opinion the only rational thing we could do now would be to stick to Manchuria and scuttle from Korea.’ Finally he refers to the naval position (pp. 230 and 241): ‘The fate of the whole campaign rested on one slender and uncertain thread— the possibility of securing at the first stroke absolute command of the sea—the night attack on Port Arthur deprived us from the outset of the use of a most important arm of defence, as well as of offence, and thereby practically determined the issue of the campaign.’

From all the above it is evident that our refusal to withdraw from Korea as the Japanese had requested us to do during the course of the summer of 1903 up to the beginning of the hostilities led to the conflict.

I can throw no light on why the frequent warnings of Baron Rosen, who in his position as Ambassador to Japan had his hand on the political pulse of that nation, remained unheeded, unless the reason was that we grossly underestimated the military strength and efficiency of our enemy. We did not take them seriously, and this was an unpardonable error.

This, in my view, is the only explanation of our nonchalant attitude to what ought to have been a manifest danger to us.

So much was this the case that, when war came to us, we were entirely unprepared and allowed the Japanese to take the initiative everywhere.

One of the very few men, however, who did take the initiative against the enemy was Admiral Makarov. Japan’s success, unlike ours, rested entirely, as the Baron has pointed out, on the control of the sea, as all her troops had to be moved to the Asiatic continent from her islands. If their fleet could only have been destroyed or crippled we might have won, as then the Japanese Army would have found itself cut off from supplies in men and munitions.

When the news of the sinking of our ships reached us, Russia was moved to violent indignation, and I think that this was possibly the only time when this war had the enthusiastic backing of the whole people.

General-Admiral Grand Duke Alexis Alexandrovich of Russia (1850-1908)

I presented myself to the Emperor and to the Grand Duke Alexey Alexandrovitch and reported for active service. At first it was suggested that I should join the staff of Admiral Alexeeff, but on Uncle Alexey’s advice I decided to report to Admiral Makarov at Port Arthur for service afloat. He had just been appointed to succeed Rear-Admiral Starck in the command of the Far East squadron at Port Arthur.

Until the appearance of the Admiral on the Far Eastern horizon, our fleet had not yet recovered sufficiently from the first onslaught by the enemy. With his arrival everything changed completely. This shows how the character of one man can instil hope and courage and the will to overcome all obstacles when all seems to have been lost and beyond repair.

The Admiral was a remarkable man not only as a naval officer but as a personality. His opponent, Admiral Togo, knew his value, and that he had in him a formidable enemy. The peculiar features of Makarov’s character were quickness in seizing a situation and making immediate use of his advantages, absolute fearlessness, which sometimes amounted to dangerous audacity, an unshakable will power to carry out his plans unflinchingly and never looking back once he had begun an enterprise. His arrival at Port Arthur had almost a magic effect and ushered in a spirit of energetic activity and of hope. He was the kind of man with whom it would be a privilege to serve.

Before leaving for the Far East and plunging right into the midst of the witches’ cauldron, I obtained the Emperor’s consent to pay a farewell visit to Nice where Ducky and Aunt Marie were at the time.[5] I stayed there four days and when the hour of departure came it was hard to tear myself away—desperately hard.

I returned to Petersburg via Vienna. On the day of my leaving for the front, I took Holy Communion in our chapel and bade farewell to my parents and to the staff of the Vladimir Palace. Then I left for the great unknown—for death maybe.[6]

I interrupted my journey for one night at Moscow, where 1 stayed with Uncle Serge and Aunt Ella.[iv] [7]Uncle Serge, as I have already said, was Governor-General of that city.

The next day I boarded the Trans-Siberian express for Port Arthur. I believe that the length of the journey from St. Petersburg to Port Arthur in miles is approximately the distance between London and San Francisco.

It was a dreary trek across very monotonous country except for some diversions at the Urals and the Baikal Lake: the latter is really a kind of inland sea called by the local people the ‘Sea of Baikal.’ We passed small stations where the train halted for hours at a time because the whole line, which was then a single track, was crowded to its utmost capacity with eastward bound troop trains. We were held up at sidings, and whenever we stopped delegations came to my carriage wishing me good luck and expressing their loyalty with enthusiasm. I did not know then how much I stood in need of their good wishes.

The train compared very favourably with the American ones on the other side of the Pacific. It was comfortable, well-heated, and the food and the wines were of the best. We fed well and slept much. I had Kube with me as my A.D.C., and Ivanov, my sailor batman; there were also a number of other officers on the train. Occasionally we made merry to pass time. Small stations were passed on the way where crowds stood on the platform and shouted. They knew that I was on the train and that I was going into the hornet’s nest. They seemed pleased that I had thrown in my lot with the rest.

And so the journey dragged on until we reached Irkutsk and the Lake of Baikal.

At that time the track of the Siberian Railway which now passes along the shores of the lake was not yet built. It was completed in 1905 and most of the way had to be blasted through solid rock. It holds the record for tunnels among Russian railways, and is a master work of skill.

The lake was frozen from end to end and the journey to a point roughly half-way across was accomplished in a fast troika drawn by sturdy little Siberian ponies. The Governor-General of Irkutsk accompanied us across the lake

For Siberian conditions the weather hitherto had been mild. There was a temporary inn half-way across the lake where we all alighted. During a short rest in this tavern, we took refreshment and warmed ourselves up with some vodka.

The Ministry of Transport had built a railway line across the ice to facilitate troop traffic; we got into one of the carriages and completed the rest of the journey. The few carriages of which the train consisted were drawn by horses as it would have been unsafe to allow a locomotive on the ice. Even then it shows how heavily the lake freezes. It was a curious sensation to be sitting in a railway carriage and be drawn across a lake, which is famous for its enormous depth. Arrived at the other side, I boarded the all-steel Manchurian section of the Trans-Siberian express, where I had a special car with a small kitchen in it, as, for some unknown reason, that section of the express had no restaurant car attached, all the feeding having to be done in station restaurants on the way.

On the other side of the lake the congestion of the line greatly increased and progress was difficult and slow.

At last, after crossing some of the dreariest landscapes I have ever seen—an endless, mutilated forest known as the ‘taiga,’ here and there interrupted by bleak snow-covered plains and frozen rivers, a picture of grey, black and white—we approached hilly and then mountainous country.

We were nearing the Manchurian frontier and the Chinga ridge across it.

A halt was made at the frontier station ‘Manchuria’ and thence the train climbed laboriously up the steep incline of the ridge, helped by an auxiliary engine from the rear. We passed through the long tunnel of the Hingan Pass and thence into the dreary and endless Manchurian landscape, passing Harbin, Mukden, and Lao-Yan. At Mukden I was met by the Governor-General, Admiral Alexeeff. There was feverish activity everywhere. The line and stations were teeming with troops, munition transports, and every conceivable thing connected with the War. A human river flowed continuously from Europe to the Pacific along the narrow steel thread of railway.

Towards the early part of March I arrived at Port Arthur. The journey had taken two weeks in all, which, considering the unusual conditions, was by no means bad.

Port Arthur looked like a human ant heap. I did not concern myself with the fortifications which were being completed, but only with the fleet.

Immediately after his arrival Admiral Makarov had started repairing the damaged units of our Navy. Expert workmen had come from our yards at St. Petersburg and were hammering away at the ships. They worked efficiently and lost no time about it. As there were no dry docks for the battleships the local engineers had improvised some on the spot. Considering the enormous difficulties of their work, our people produced surprising results. After about a month of hard work most of the ships had been put into a condition which made them fit to meet the enemy.

Much has been written about Russia since the Revolution, more of it stark nonsense than truth. Our engineers and workmen were equal to any.

When the War broke out on that fatal 8 February, Port Arthur had not been completed as a naval base. Its inner harbour had only one basin where ships could float during low water, while the rest had to lie high and dry on mud like a lot of ducks. Space was cramped and the entrance to the harbour was only about a hundred yards across from end to end, allowing only one ship to pass at a time. A more awkward place could not have been chosen. It was, as I have already said, a death trap.

Admiral Makarov’s predecessor had taken twenty-four hours to move his squadron out into the open, a manoeuvre which could only be done during high tide—Admiral Makarov took only two hours and a half, and within two days of his arrival our destroyers were already engaging and worrying the enemy. The demoralizing inactivity of our fleet had been broken as though by a spell through the energy of that remarkable man. He was a great psychologist and knew perfectly well that results could only be achieved by showing his officers and men what they could do. He broke the atmosphere of defeatism entirely and on 11 March the whole squadron engaged the enemy. Very unfortunately three of our best cruisers had been cut off at Vladivostok by the outbreak of War, but even then we had something with which to oppose the Japanese grand fleet, even though we were outnumbered and outclassed by them. We could worry them and impede their troop transport, and although in fact we were doomed, yet so long as our squadron remained active, we could help our land forces by delaying the enemy’s landing of troops, and give our armies a chance to accumulate.

Sunken Japanese ships blockade the inner harbour of Port Arthur, 1904

The Japanese fully realized our importance and made a number of efforts to block the inner harbour by sinking ships across the narrow entrance as the British succeeded in doing at Zeebrugge during the Great War.

Our forts were built along the hills encircling the inner harbour, and a good view could be had far out to sea. If anything suspicious was seen moving about at sea during the night searchlights would comb the darkness with their beams.

The vigilance of our forts prevented the Japanese from blocking the entrance. They were always surprised by us. If anything suspicious was observed, searchlights were switched on to the scene of the enemy’s activity and a fearful din would shake the night, as the shore batteries opened fire from their heavy guns. Long and uncanny beams, flashes of red and orange, and rockets of varying colours lit up the night, in which the Japanese went about their business of bottling us up as though little were amiss, as a firework of destruction. Nothing could stop them. They did sink their ships all right, but never across the harbour entrance, and on one occasion several of their vessels ran on to some rocks with the loss of their crews. At other times, the Japanese would bombard us from the sea in the hope of disabling our ships in the inner harbour. Their projectiles were fired across the surrounding hills and our shore batteries joined in the concert. As we were right among these steep hills, we could not at first get a sufficiently high angle of elevation for our guns to fire projectiles across the intervening hills at the enemy out at sea, and thus had the demoralizing experience of lying about inactively like a lot of clay pigeons and allowing ourselves to be shot at without being able to reply.

Finally the Admiral devised a way of getting over the difficulty. He had his ships tilted over to a certain angle which increased very considerably the furthest angle of elevation attainable under ordinary circumstances. Our observation post in the forts would communicate to us the particular squares in which the enemy vessels were and, as with this new device we could fire clear of the hills, we succeeded in scoring hits on a number of occasions. So successful, in fact, did this method prove, that two of the Japanese ships were badly damaged and thereafter they left us alone.

Postcard of the Imperial Battleship “HIMS Petropavlovsk”, 1904-1905

About a week after my arrival I was appointed to the Admiral’s staff aboard his flagship, Petropavlovsk. I was in constant and very close touch with him. He gave me much work to do, most of it of a confidential nature, and thus I obtained a good insight into what was going on.

Occasionally I had to rush off to one or the other of our shore batteries to stop them from firing at our destroyers at night. No lights were allowed and whenever our destroyers went out to sweep or lay mines or on patrol duty, there was nothing to distinguish them from the enemy. Our smaller ships were out nightly on various duties, as well as during the day time.

Meanwhile, the Admiral was preparing for a sortie with the whole of his squadron, to break through the blockade and to join his forces with the rest of the fleet at Vladivostok. Every night the Admiral had one of his ships anchored in the outer roads of the harbour between its entrance and our mine barrier. The idea was to prevent the enemy from taking us by surprise with a night attack and to watch out for any of his ships when they came to lay their mines. If any suspicious activity of any kind was observed, he would have the sea searched for enemy mines at daybreak.

The Admiral spent his nights on board the particular vessel whose turn it was to guard the harbour entrance. At the same time a careful watch was kept by our people in the forts.

On 12 April the sea was rough and visibility exceedingly poor owing to a violent blizzard. At 6 p.m., Admiral Togo dispatched some of his destroyers to lay mines outside Port Arthur at night.

At II p.m., these arrived at their destination and discharged their mines successfully. They had, however, been noticed by our forts, which shone their searchlights on the area of their activity, but owing to poor visibility were unable to retain them in the radius of their beams.

The cruiser Diana with the Admiral on board was on duty that night. I remember that I slept fully dressed on a sofa in the mess-room of this cruiser.

The observation post in one of the forts had warned us that suspicious objects had been spotted out at sea and thus we were fully aware of the situation. Makarov intended to have the sea searched for mines at daybreak, when an untoward incident diverted his attention elsewhere.

He had made it his principle that he would not allow himself to lose any of his ships before the day when the whole squadron would engage the enemy in a major battle.

During the night of 13 April he had dispatched a number of his destroyers to search for the whereabouts of the Japanese grand fleet, which he soon hoped to be able to attack.

During the blizzard that night two of our destroyers became detached from the rest. The destroyer Strashnyi[v] thought that it had found the other destroyers and joined their line. At daybreak its commander, Mallejev, saw to his horror that he had mistaken, owing to the poor visibility, the enemy destroyers for Russian ones and that he was following in their wake.

The Japanese engaged him at once. Mallejev kept them at bay until his ship was holed through and through, his guns put out of action, and his engines destroyed. He defended his ship to the bitter end with a machine-gun and then the Strashnyi disappeared beneath the waves. Mallejev succeeded in jumping overboard, wounded as he was.

The other Russian destroyer, the Smelyi,[vi] had found our ships during the night and had warned the Admiral of the danger in which the Strashnyi was.

Makarov, true to his principle, at once dispatched the cruiser Bayan to save the Strashnyi. The Bay an arrived just in time to pick up a few survivors from the sea, at the same time firing with her port guns at the enemy.

Makarov realizing the perilous situation of the Bayan decided to come to her rescue without delay.

I accompanied him to his flagship, the Petropavlovsk, as soon as she emerged from the inner harbour. If the Bayan was to be saved, no time could be lost, and for that reason the Admiral decided to meet the enemy with only a few ships, as the rest of his squadron were still getting up steam.

The Petropavlovsk led the Poltava, Askold, Diana, and Novik, which were flanked by destroyers. We proceeded full steam at the enemy.

Meanwhile the Bayan, having finished her rescue work and hitherto successfully warded off all enemy attacks, joined our line

The sea by then had calmed down considerably and visibility was moderate, but it was bitterly cold.

Suddenly a number of large enemy vessels appeared on the horizon. The leading one was almost instantly recognized as the Mikasa. She, with the rest, was steaming full speed at us, scattering foam from her bows.

At first only the Mikasa and a number of other enemy ships had been clearly discerned, but a few' moments later it became obvious that we had the whole of the grand fleet after us. Makarov was undismayed by our inequality and seemed at first willing to engage the enemy fleet with his five ships. I, and his flag captain, told him then and there that in our view it would be sheer folly to do so. Markarov then wheeled his line and took course for Port Arthur, where he was going to order the rest of the squadron to join him in engaging Togo’s ships. While waiting for them to scramble out of the inner harbour, we were in the shelter of our shore batteries. Meanwhile Togo, who had been gaining on us considerably, was still coming on. His line included two of the most modem ships of the time, the Nishin and Kasuga. They had just joined his fleet, having recently arrived from Italy, where they had been built.

The Pobieda and the Peresviet had already joined us, while the rest of the squadron were coming out one by one.

I was standing on the starboard side of the bridge of the flagship talking to that famous painter and war correspondent, Vereshchiagin[8], who was sketching groups of enemy ships. Lieutenant Kube was with me.

The Admiral, Rear-Admiral Mollas and two signallers were standing on the port side of the bridge, signalling to our ships, while they were leaving the harbour, which stations in the line they were to take up.

Meanwhile we were manoeuvring to adjust our position at the head of the fleet, when Vereshchiagin suddenly turned to me and said: “I have seen much fighting and have been in many a tight corner, but nothing ever seems to happen to me.” Apparently he was looking forward to the scrap. ‘You wait and see’—I thought to myself as he was still merrily sketching away.

It was about ten o’clock. Lieutenant Kube said to me: ‘‘I am going down below, sir, to have a cup of coffee while we are waiting for the rest to get into line.” “Don’t,” I said. “You had better remain up here.” But he went as he wanted to have a quick ‘tuck in,’ having had no breakfast that morning.

The Battle at Port Arthur, 1904

On the Admiral’s side of the bridge they were still signalling, when suddenly there was a terrific bang, a fearful ‘puff’ ‘as though a thousand giants simultaneously had said “Phoo.” ’ It was as though a typhoon had suddenly released all the pent-up forces of its violence. This blast was followed by a dull concussion which made the large vessel shake from stem to stem as if a volcano had erupted immediately beneath it and a roaring wall of red fire rushed up within a foot from where I was standing.

Everything gave below my feet and I felt like one sus¬pended by some uncanny force in mid air. I was badly burnt on my face and was bruised all over. Rear-Admiral Mollas was lying on the bridge with his skull crushed in among the signallers, who were either dead or badly wounded.

I rushed forward instinctively, clambered over the rail, dropped on the roof of the twelve-inch gun turret and thence on to a six-inch turret below. The Petropavlovsk was by then heeling over to port. For a moment, only for a flash of a moment, I stood reflecting what to do next. To port a gurgling and foaming sea was rising rapidly, churned up into ghastly whirlpools by the motion of the vessel, which was turning turtle with great speed.

I realized, as her hull was rolling over, that the only chance of escape lay to starboard, where the water was nearest, for otherwise I would be caught by the suction made by the capsizing vessel. I jumped into the fearsome ‘maelstrom.’ Something struck me a violent and stunning blow in my back. There was the sound of a hurricane around me. Then I was seized by the uncanny force of a swirling whirlpool. It gripped me and dragged me into the black depth of its funnel. Round and round I went with a mad, corkscrew-like motion, rushing round in ever-narrowing spirals until all around me became dark as night. All seemed lost now. It is the end! I thought. There was a short prayer and a last thought for the woman I loved. Meanwhile, I struggled violently against the force that held me in its fearful grip. At last, after what had seemed an eternity, its tension decreased. Light pierced the darkness feebly and grew stronger. I struggled madly and suddenly broke surface.

Something struck me. I gripped at it and held on for dear life. It was the roof of our steam launch that had got adrift. I pulled myself up and reaching out caught hold of its brass railings.

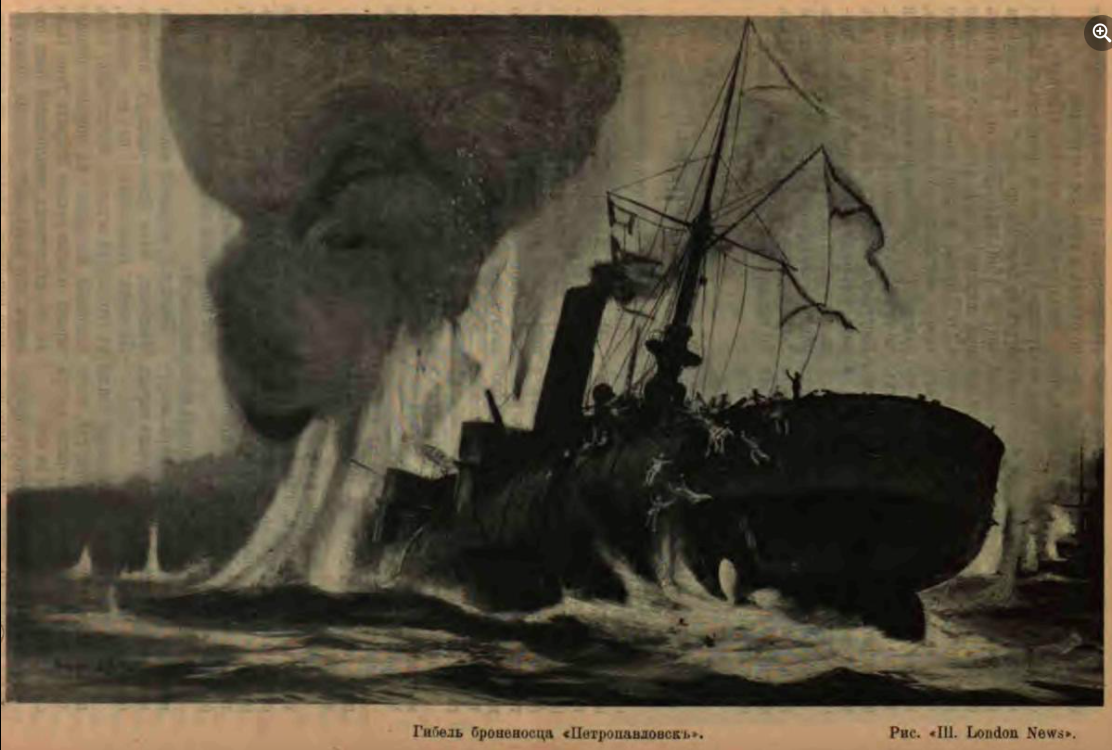

“The destruction of the Petropavlovsk” watercolor by an unknown artist, ca. 1904

I had been more than lucky to have dived up at that distance from the flagship and at that moment, as otherwise I would have been caught and drawn under without a chance of escape by the suction created by the sinking vessel.

What had saved me were my clothes. I have already said that it was bitterly cold, and the water, incidentally, was just a few degrees above zero. I was dressed in a padded coat, underneath which I had a fur-lined jacket and an English woollen sweater. This very likely gave me some buoyancy, otherwise I would have gone to join the rest of the six hundred and thirty-one who perished.

The other ships of our squadron which were nearest the sinking flagship, which by now was taking her final plunge bows down, stem high in the air, and engines still working, had lowered their boats and were combing the sea for survivors.

One of our destroyers’ whale-boats was quite near me. They noticed me and pulled in my direction. I shouted to them, I remember: “I am all right as I am, save the rest.” They pulled me out and into their boat and in the effort, owing to the weight of my soaked clothes, nearly crushed my chest against the gunwale of their boat. It was filled to its utmost capacity with other survivors.

I was transferred to another boat, which took me to the destroyer Bezstrashnyi,[vii] where they laid me on the bed in the captain’s cabin. I caught sight of the captain, whom I knew. I saw him and the rest through a haze which was settling down over me. They gave me some brandy and vodka and then I broke down completely. I was asking them repeatedly: “When are we returning to harbour.” Meanwhile the Japanese were shelling the squadron, making use of the temporary confusion.

Soon I came to. We had got alongside the quay of Port Arthur, and before I was helped off the destroyer I was asked whether I would like to see the captain of the Petropavlovsk. I was not anxious to see anyone in particular, and in any case he was lying like one dead without any sign of life stretched on the table of the mess room.

Another view of the sinking of the “Petropavlovsk” originally from the Illustrated London News, 1904.

When I stepped on shore my brother Boris was there to meet me. We fell into each other’s arms. It appeared that he had been watching the squadron from one of our forts when the disaster occurred, and this is what he says:

‘At about 5 a.m. on 13 April we were woken up and told that the Japanese fleet had been sighted and that ours was preparing to leave the harbour to meet it.

‘Prince Karageorgievitch and I went towards the port and on our arrival there ran into Admiral Makarov and Lieutenant Kube. Makarov, I remember, said: “Good morning—we are pushing out presently.” They were in a great hurry and the activity on board was such that, although Cyril was searched for, the Petropavlovsk cast off without my having taken leave of him. Prince Karageorgievitch had suggested to me that we might go on board as it was a golden opportunity to witness a fight at sea. Fortunately we did nothing of the sort.

‘From the port we rode to the top of the “Golden Hill,” from which an excellent view could be had out to sea. We arrived in time to see some of the ships of our squadron crawling out of the narrow entrance of Port Arthur below. We watched them until they almost disappeared from view. Suddenly a great deal of smoke appeared on the horizon, but not from where our squadron was still faintly discernible. It was clear to us that an encounter with considerable Japanese forces was imminent, and almost at the same time the rolling thunder of big guns in action heralded the beginning of a battle. The ships of both forces became clearer as they drew nearer to Port Arthur. It was obvious that Admiral Makarov had met superior forces and was withdrawing his ships to Port Arthur, where he could await his reinforcements in the shelter of our batteries. Judging from what we could see of the enemy and the smoke from his ships, it was fairly clear that the Admiral must have come upon, if not the Japanese grand fleet, then at least some very considerable force.

‘When at last our vessels anchored immediately below where we were, in the outer roads of Port Arthur, we were greatly relieved of our anxiety for their safety. They had had a race with the enemy, who had tried to catch them before they reached the shelter of our forts, and who had, in fact, gained on them considerably. It was one of the most stirring and exciting experiences imaginable to watch these momentous doings unfold themselves below one like on a stage, and yet this was a game of death.

‘Prince Karageorgievitch, Serge Sheremetieff, and I went down to the signalling post below our batteries to find out what was being done on board our ships and what the Admiral intended to do next. We might get some indication of this from a signaller. We were told by the sailor, who was reading and answering signals from the flagship, that the Admiral had ordered munition to be removed from all guns and that officers and men of all ships were to be fed. Then I remembered that we, too, had not eaten anything that day. Serge Sheremetieff offered me some dry prunes. Suddenly there was a terrific detonation and the same signaller who had told us of the recent dispositions by the Admiral shouted: “Flagship blown up!” Where the Petropavlovsk had been but a few seconds before there was now nothing but a sinister pall of black smoke. Then there was another fearful explosion; and about a minute later, when some of the smoke had cleared away, we saw that the Petropavlovsk was disappearing into the sea bows first with her propellers turning in the air as her stem pointed skyward. It was a fearful impression, a ghastly nightmare. Cyril was on board—and from the momentary impression of this terrifying sight, one thing was clear to me, that no one could have possibly survived this wreck.

‘We hurried down to the harbour, where no one knew anything about survivors. There was no news of any kind apart from the fact that the destroyers near the place of the disaster had put out their boats and were searching the sea. Great depression and pessimism expressed itself everywhere. I returned to my train in a fearful state of dejection, convinced that my brother Cyril had perished. Indeed, the very thought of the contrary, in view of what I had seen and heard, seemed idle. In about an hour and a half a naval officer rushed up to my train and announced that my brother had been saved, that he was on board the destroyer Bezshumnyi,[viii] and that he wished to see me. This incredible news seemed to be too good to be true. I refused to believe him, but he gave me his work of honour that it was true. I hurried back to the port and on board the destroyer. All the time I found it hard to believe that he had really escaped from that colossal disaster, and yet it was true, and when I saw him I experienced that unique sensation of absolute relief after a great burden of fear has been removed from one. Considering what he had gone through, he looked in comparatively good condition. I took him to Harbin in my train.’

A Japanese woodblock print of the Battle of Port Arthur showing a Russian ship hitting a mine, ca. 1905

The Petropavlovsk had run on an enemy mine, one of those which Togo’s destroyers had laid during the previous night. The explosion was followed by the detonation of all our magazines and torpedoes, which knocked part of the bottom out of her. At the time of the detonations all her funnels, masts, and other parts had come hurtling down upon her decks and bridge. I do not know how' I escaped all this. Of the 711 officers and men, only eighty were saved in all. Admiral Makarov perished with the rest, only his coat was found floating in the sea. With him perished all the plans of his intended operations as well as the whole of his staff except myself and a few others. His death sealed the fate of the whole squadron. Thereafter all further efforts to break through the blockade that were attempted did not succeed. The subsequent history of the squadron was to be nothing but a prolonged agony of a bottled-up fleet. The master-mind and its inspirer had gone. Gloom settled down over all things in Port Arthur. The only man who could have done something was no more.

The Japanese as usual had had luck.

Kube, the friend and constant companion of my youth and of all my voyages, had perished, as did many of my other friends—they have no grave but the sea.

A few minutes after the disaster there was another fearful detonation. The battle-cruiser Pobieda had run on a mine. She was, however, hauled off into Port Arthur.

Even after this disaster our doomed squadron succeeded later in engaging the enemy and giving them a severe ‘hammering.’ It failed, however, to break the blockade and was scuttled when, after a heroic defence, Port Arthur fell to the enemy.

I boarded the Trans-Siberian express and left sinister Port Arthur behind me. I was in no fit state to be of any use for active service. Badly burnt, the muscles of my back strained, suffering from shell shock, and in a state of complete nervous collapse. I was for the time being an absolute wreck.[9] [10] [11]

Nicholas II, Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich, and Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich, ca. 1900

At Harbin I received a visit from General Kuropatkin, our Commander-in-Chief in the Far East, and also from Admiral Alexeeff.

The disaster which had befallen our fleet and the loss of Admiral Makarov had produced the worst effect on the Army, having serious repercussion on our troops. The Admiral could not be replaced by anyone.

Arrived at Moscow I was met by Uncle Sergey[12]. It was the last time I saw him, for during the next year the Revolutionaries murdered him, because, while many of our administrators had lost their heads, he had kept his and had gone about his duty energetically. My brother Andrey had forwarded packets of letters and telegrams from Ducky, which reached me in Moscow as well as along the line.

I did not interrupt my journey there and continued straight for St. Petersburg, where members of the Imperial Family gave me a very charming reception as my train drew into the station.

A few days later I had an interview with the Emperor.[13] It struck me as odd that he did not inquire either about the Petropavlovsk disaster or about the Admiral, nor did he refer to the war or ask how it was progressing. The conversation was confined to an exchange of the usual politenesses which generally concern themselves with health and weather. He seemed tired and overwrought. He gave me permission to go abroad as soon as the doctors allowed me to do so.[14]

Grand Duchess Victioria Melita and Princess Alexandra Hohenlohe-Langenburg, ca. 1897

I went off to Coburg and when I arrived at the station Ducky with her sister, the Princess Hohenhohe-Langenburg, was there to meet me. They were dressed in white for the occasion. I will never forget this reunion. I felt like one who was returning from the land of the dead to new life. It was a fine spring day—and there was spring in my heart too.

To those over whom the shadow of death has passed, life has a new meaning. It is like coming out of the darkness of a mine back to daylight. And I was now within visible reach of fulfilment of the dream of my life. Nothing would cheat me of it now. I had gone through much. Now, at last, the future lay radiant before me.

I will pass over this summer as it belongs to one of those very intimate and lovely episodes of one’s life which are part of that secret recess in one’s memory that cannot be shared with the world.

Suffice it then to say that this period was even gayer and more jolly than any of my previous stays at Rosenau. The good people of Coburg knew that I was courting their princess and treated me as one of their own wherever I went.

In the autumn I returned to Russia, where I joined the staff of the Admiralty.

My activity in the Admiralty was confined to some advisory work on a new type of destroyer which was being planned, and was neither exacting nor interesting.

For some time past the Press had been proposing the entirely unpractical and absolutely quixotic scheme that we should send our Baltic fleet to the Far East to relieve the squadron at Port Arthur and establish naval supremacy there.

They made such a noise about it and were so insistent on proclaiming this ‘brain wave’ of theirs, that finally, and goodness only knows why, the Admiralty approached the Emperor with this ‘brilliant’ idea. The most that all these people could have done would have been to cover their madness with a cloak of secrecy. They did nothing of the sort. By the time the first steps were taken to materialize this scheme, the whole of the world, including, of course, the Japanese, knew every detail about the ships which were going to be sent on this ‘Mad Cap’ errand.

The most capable of our admirals was charged with the execution of this plan. I have already referred to Rojdestvenski. He duly informed the Emperor that, in his view, the plan was doomed to failure from the very beginning. Firstly, because we had no ships, barring a very few, with which we could oppose the Japanese Navy on equal terms, even if the whole fleet were overhauled and modernized, for which there was precious little time left. Secondly, because England, who had command of the sea, and who was an ally of Japan, would do her best to impede the Baltic squadron wherever and however she could, along the twenty thousand miles of the voyage. Thirdly, because such an armada, consisting largely of old ‘crocks,’ would be impeded in its progress by frequent breakdowns and would need a formidable retinue of auxiliary vessels and so forth. Then there was the essential question of coaling. Would the neutral powers and even those who, like France, were allied to us, dare to offend Britain by helping us? A fleet, once it is without a base, is at the mercy of chance. The whole scheme was beset by difficulties of the most formidable kind. It was a fantastic conception, the like of which had seen no precedent! The whole of this armada had in all about fifty ships. It would need provisions, coal, spare parts. Repairs would have to be done at sea. Some of the ships were entirely unsea- worthy even in the Bay of Finland. They belonged to that scrap-heap which I have already described in connection with the gunnery school. And all this was to go to the Pacific through tropical seas!

The Admiralty seemed undismayed. Their attitude amounted to that kind of negligence which owing to its blatant disregard for natural consequences might be called ‘criminal.’

They were intelligent beings, and must have foreseen that they were sending thousands of our best sailors to certain death. A fleet was being dispatched to add to the glory of the Japanese flag and to the humiliation of ours, because the Press insisted on it!

When the Admiral saw that his warnings remained unheeded, he set about his task at once. There was feverish activity in all our munition works in the land. Day and night the blast furnaces in the south were turning out the steel plates and guns as the great hammers knocked them into shape. Trains full of the necessary equipment arrived at Kronstadt and the old ‘crocks’ were being modernized.

Meanwhile the Press was busy in supplying the world with all the smallest details of the progress of the work and Togo was laying his plans accordingly.

At Kronstadt everything that could be got together was being assembled until the fleet was ready to leave for its destination. If it had not been for the Germans, who undertook to provide us with coal all along the twenty thousand miles of the voyage, the fleet would never have got beyond West Africa.

Shortly before Rojdestvenski set out from Libau on 17 October 1904 I accompanied the Emperor as his A.D.C. to the Admiral’s flagship, the Souvoroff, where a conference was held.

I was not present during this meeting, and, therefore, do not know what happened apart from its result, which sealed the doom of thousands of my compatriots. The Admiral had discharged his duty brilliantly, but the whole world ridiculed him. There were bets in all capitals that this fleet would never be able to reach its destination. We were made the laughing-stock of the world. All the naval experts laughed us to scorn. The ‘Russians are no sailors,’ so they said, and ‘this armada of tubs will never get beyond the North Sea,’ and when the Dogger Bank incident occurred there were hoots of sarcastic laughter. ‘The Don Quixote had mistaken inoffensive North Sea trawlers for Japanese destroyers and had engaged them in earnest.’ War with England was imminent!

Much has been written about this incident. I was not present, but, from my knowledge of the man, I can state that Rojdestvenski was a very capable officer. This he proved by taking the whole of a large fleet in the most difficult conditions possible to a battle at the other end of the world in perfect order, without losing one of his ships and—what kind of ships!

This epic feat was properly appreciated later.

When the whole of the Baltic squadron passed Singapore in perfect formation the St. James' Gazette wrote: ‘We have underestimated the Admiral and greet him with that respect which valour deserves,’ or words to that effect[15]. Before the squadron left Libau he had been warned apparently that the Japanese had bought a number of destroyers in Britain, where they had been built for a certain South American country, and that they intended to provoke an incident in the North Sea which would either plunge us into a war with Britain or else force us to recall the squadron forthwith. If this was so, then it was a brilliant political move on their part. The Admiral set out fully prepared for any event of the kind. There is little doubt that there were a number of suspicious vessels resembling destroyers, and carrying no lights, among the trawlers, as independent evidence from our ships, as well as from the crews of some of the trawlers, showed during the investigation by the International Court which examined and tried this incident.

If these suspicious vessels—one of which remained for several hours at the place where the incident occurred when all our destroyers, without exception, were already nearing Dungeness—had attacked the squadron first, the Admiral would have been held responsible for the damage resulting to his ships, as well as for his negligence in allowing himself to be attacked. If, on the other hand, he attacked first, as, in fact, he did, then owing to the great number of trawlers that were about and owing to the absence of light on the suspicious vessel, damage was sure to result to neutral shipping and that would put us in a difficult position. If that be so, it was a Machiavellian plan! [ix]

And if this is what really happened, and there is much evidence in support of it, the Admiral acted properly in the dilemma in which he found himself, and no blame is attached to him or to our fleet.

Even though our ships were nearly all destroyed in an unequal contest on 27 May 1905 in the Straits of Tsushima, where our ‘tin pots,’ out-ranged and outdone in every conceivable way, put up a heroic struggle and battered the enemy considerably before they were sunk, this epic story of a doomed fleet sailing to certain death and fighting to the very last gasp, after a voyage of unprecedented length, stands alone of its kind among the naval annals of the world.

The Admiral had been badly wounded during the battle and was a dying man, and when he was returning to Russia after his captivity in Japan, even the Revolutionaries cheered him and ran up to his train to see the man who had not spared himself.

But what did the authorities do with Rojdestvenski? They court-martialled him! For having taken a scrap- heap to order across the sea to Japan and for having lost it there. If this were not true, it would sound fantastic!— they condemned this man for having loyally carried out the Gilbertian plans of their own concoction. Two years later he died broken in body and in spirit.

In conclusion, I may add that the gunnery of our ships at the battle of Tsushima left nothing to be desired. They were most effective in finding their range and in hitting their objectives, if, from Japanese accounts, one is to judge by the hits they scored. Had our shells been of the same design as those of the Japanese, that battle might have had a very different result. The Japanese shells exploded at the slightest contact, even when they hit the surface of the sea, while ours were designed to burst only when hitting armour plate, and when they burst they split into clumsy fragments. The Japanese shells, on the other hand, produced a fearful effect on exploding, splitting into minute and glowing splinters which set everything combustible on fire. The force of their detonation was such that heavy armour plate was twisted like corkscrews by them and roofs of gun turrets were blown off as if made of wood. Further, they contained a chemical which was the precursor of poison gas. It is mainly due to their shells that our fleet was handicapped from the beginning in spite of its inequality in modern ships.

It was my intention all the time to rejoin the Navy on active service in the Far East as soon as my health permitted. The news from Rojdestvenski’s fleet was good. Hitherto all had gone well with him, and he was approaching Japanese waters. In spite of the overwhelming odds against him he had, hitherto, overcome all obstacles on his way which human agency and wind and weather had put against him, and there was one slender chance which I knew might still come to his aid and enable him to escape from the clutches of his opponent Togo. The Sea of Japan, as well as the whole region between it and Vladivostok is, as I knew from my experience there, frequently given to fogs due to the meeting of warm and cold currents. With luck, the Admiral might pass through the narrow seas between the islands of Japan and Korea in a dense fog and thus break through to his goal without a battle. I intended to go to Vladivostok where we still had a few first class ships, and where I would await the arrival of the Baltic squadron and resume my duties with them.

The Admiral did, in fact, very nearly pass through the Straits of Tsushima and the Japanese fleet, unseen and unscathed. It was a matter of one day. Had he passed through them on 26 May, which was very foggy, instead of on the 27th, as he did, he would have broken through successfully as visibility was exceedingly poor. But on the 26th he had to crawl along with his fleet at a few knots owing to engine trouble in one of his ancient ships, which had joined him in Cochin China where, for a month, he had had to await their arrival.

Protopresbyter Ioann Leontievich Yanyshev (1826-1910)

When the news of the disaster reached us, my journey to the Far East lost its raison d'etre. During my stay in the Capital, I had a consultation with Father Yanysheff, the Confessor of the Empress, concerning the degree of relationship between Ducky and myself, as I had now decided to bring this matter of our marriage to a head. I considered that it would be easier for the Emperor to make a decision if he were to be confronted with a fait accompli. Father Yanysheff assured me that from the point of view of Canon Law there was not the slightest obstacle.[16] This encouraged me considerably. Accordingly I prepared the plans for our wedding, the date for which depended on the conclusion of hostilities between us and Japan. Practically the whole of that year I spent in Germany, mostly at Coburg, with some occasional visits to a sanatorium near Munich, where I was under treatment for my nerves which had been very badly shaken by the Petropavlovsk disaster. During that period I had my first impression of Bayreuth, where Ducky and I motored from Munich. We got into the very holy of holies of its musical elite and met ‘Cosima’ Wagner, the widow of the great composer. She was a daughter of Liszt. Then there was a very jolly visit to Schloss Langenburg in Württemberg, the family seat of the Hohenlohe-Langenburgs.

All our travelling in Germany was done by car. It was the autumn of the year 1905 when we decided to marry.

That autumn the Treaty of Portsmouth was signed, and we owe it in no small measure to Count Witte, who had been rehabilitated, that we lost so very little as the result of this war.

On 8 October Aunt Marie’s spiritual adviser, Father Smirnoff, arrived at Count Adlerberg’s house at Tegemsee near Munich, which we had chosen for the place of our wedding.

It was a very simple occasion. There were present Aunt Marie, Cousin Beatrice, Count Adlerberg, Herr Vinion, Aunt Marie’s gentleman-in-waiting, her two ladies-in-waiting, and the Count’s housekeeper.[17]

Haus Adlerberg am See, Tegernsee, mid-20th C.

My dear Uncle Alexey Alexandrovitch, who had stood by me in all my troubles, had told me on one occasion that if ever I stood in need of his help, I had only to let him know and he would do all in his power to help me. I will never forget his constancy in my cause throughout the dark period which now lay behind me.

He was in Munich at the time and I wired to him to come as soon as possible to Tegernsee, but did not tell him the reason.

We held up the wedding, as I wanted him to witness it for us. As he did not appear, we were married without him. Father Smirnoff was very scared, as he feared the wrath of the Holy Synod and the Emperor.

We were married in the Orthodox Chapel of the house on 8 October 1905.

And thus we were at last united as man and wife to go together along the path which lay before us and which was to lead us through much joy and great adversity.

There are few who in one person combine all that is best in soul, mind, and body. She had it all, and more. Few there are who are fortunate in having such a woman as the partner of their lives—I was one of these privileged.

The ‘Wedding Feast’ had been in progress for about half an hour. There was a blizzard raging outside, when Uncle Alexey arrived in the midst of it all. It was curious to see his amazement. This great giant of a man, so reminiscent of Uncle Sasha[x] in character and appearance, was at first dumbfounded, then he congratulated us warmly.

Apparently he had been chasing round Munich for a tarpaulin for his luggage, which he had piled up on the roof of the car, and had not succeeded in finding one. Tarpaulins, I presume, are more of a thing pertaining to the sea near which they abound rather than in a city like Munich. He complained that one of his new cases had been ruined by the blizzard.

He added to the gaiety of this occasion with his open, breezy personality and huge voice.

Grand Duke and Grand Duchess Kirill Vladimirovich in exile, 1906.

Footnotes

(2024)

[1] It is interesting to compare this statement with a letter of Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna’s of 15 April 1903: “Kyrill wants to come soon again to Coburg, but Uncle Wladimir does not approve of it and I see a great many conflicts arising from it.” It seems clear that Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich was playing two sides of a coin with his sister, telling her what she wanted to hear, while actively working on his son’s behalf.

[2] There is a record in the Kammer-Fourrier Zhurnal that the Emperor indeed met with both Grand Duke Vladimir and Grand Duke Kirill in June 1903, but the details of that meeting are unknown. What we do know is that the Emperor, after having previously instructed Kirill to break off his engagement twice and to cease seeing her, nevertheless allowed him to return to Coburg to spend time with Ducky. Whether he intended to or not, it appears that he left the impression that things might be on the mend.

[3] Letter from Grand Duchess Marie to Queen Marie of Romania, 29 June, 1903: “Dearest Missy! Though I have not heard from you for some time, I must write a few words from our dear old Gotha. We came here for two days, as I wanted Kyrill to see it and also for a little change, as the couple always sticking together rather bores me and it is good for my amiable nephew to have a little knowledge of Germany. I cannot say he is prejudiced against this country only he knows nothing about it and speaks very little German. Ducky is calm and in better spirits, though their affairs have not advanced much as Nicky will not consent to the marriage. But Kyrill being decided more than ever to do it, I see it coming and even soon. But how and where, this is all vague and difficult to combine. No open marriage, but some secret one. Yet, Kyrill says he won't do it without telling Nicky, but take all the consequences on him. So we live at present in a sort of fool's paradise, putting off the evil hour of decision!...’ (Mandache, p. 99)

[4] It was, in fact a very difficult Christmas. In November of 1903, Ducky’s daughter had died at Spala in Poland, and the ripple effect of the death was felt throughout the courts of Europe. Grand Duchess Elizabeth wrote to Grand duchess Ksenia: “Oh, it is all so sad, so sad – you can’t put it into words… Thank God that she did not suffer and went easily, without anguish – went to another world…and returned to the little angels… The meeting with Ducky went well. She looks like a shadow – a poor, grieving woman. The child would have been with her if not for the connection with K[irill]. Will he marry her?” (GARF, f. 601, op. 1, d. 1263, ll. 1-2 vol.)

[5] This was the second time the Emperor had given his consent for Grand Duke Kirill to meet with Ducky abroad after his meeting with Grand Duke Vladimir and Grand Duke Kirill the previous year.

[6] “There was a touching scene at the Nicholas railroad station this evening when Grand Duke Cyril (eldest son of Grand Duke Viadimir, the Czar's uncle) left for the Far East. Grand Duke Cyril returned to St. Petersburg this morning, and went to take leave of the Czar this afternoon. Grand Duchess Marie, Cyril’s mother, broke down at the last moment and wept as she embraced her son. Even the veteran Viadimir, Cyril's father, shed tears, and Grand Dukes Boris and Andrew held their brother in a long embrace. Grand Duke Cyril is going to Port Arthur to act as Chief Officer of the Flagship.” (New York Times, “Czar Takes Sacrament: Members of Royal Family Participate - Grand Duke Cyril's Departure.” 28 February, 1904, p. 2)

[7] “Aunt Ella” Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna of Russia (b. 1863-1918)

[8] “Vereshchiagin” Vasily Vasilyevich Vereshchagin (Russian, b. 1842-1904) was one of the most famous Russian artists and one of the first Russian artists to be widely recognized abroad. He was well known for his graphic and realistic pictures of the horrors of war. Vereshchagin was invited by Admiral Makarov to join him aboard the Petropavlovsk. Both Admiral Makarov and Vereshchagin were killed in the sinking.

[9] From the Emperor’s diary: “March 31st. Wednesday. In the morning came the heavy and inexpressibly sad news that when our squadron returned to P[ort] Arthur … [the] Petropavlovsk came across a mine, exploded and sank, killed: Adm[iral] Makarov, most of the officers and crew. Kirill, slightly wounded. Yakovlev, the commander, several officers and sailors — all wounded — were rescued. The whole day I could not recover from this terrible misfortune…”

[10] The news reached Russia almost immediately: Grand Duchess Ksenia, Diary, 31 March/12 April 1904: “A nightmarish day - the worst since war was declared. The Petropavlovsk, together with Makarov/ have been blown up by a mine with all their crew, everyone was killed, except Kyril and 6 officers as well as around 40 lower ranks!! Makarov put to sea early in the morning with the rest of the fleet, and on sighting the enemy began to pursue them, but when the number of enemy units increased to 30, they returned to harbour, at which point the battle ship Petropavlovsk ran into a mine, which destroyed it. Poor Vladimir, he was terribly distressed, and kept repeating that it was a miracle Kyril was alive - and how! Aunt Michen was found in tears, she is calmer now, but the first shock was terrible because it was so unexpected. The whole family started to arrive later, and at 2 o'clock there was a Te Deum. (From there I wrote a note to Mama, informing her of the Te Deum, it was the first she knew of anything, she was of course terribly upset and shocked, and it was just before a reception!) Maylunas & Mironenko, p,241)

[11] From Nice, Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna wrote to Queen Marie of Romania, 14 April, 1904: “Dearest Missy! A few words about this terrible catastrophe that nearly cost Kirill’s life. We spent yesterday a hideous day of anxiety, as in the morning, André telegraphed that Kirill’s ship was blown up, that he was wounded and coming home. Nothing more till about 6 in the evening, when a charitable old lady telephoned from Cannes, that Kirill was only slightly wounded and escaped as if by miracle. Only whilst we were at dinner, I got an answer from Niki, that the ship was blown up with Admiral Makarof and nearly everybody on board, but that Kyrill was safe on his way to Mukden with Boris. This morning more news from André, that Kyrill was burnt about the neck, probably by the flames of the explosion, but was feeling well, anyhow he does not seem to be really seriously hurt and is coming home now. But this I also don't understand, how he can be leaving the war if he is not seriously injured? I wonder he has the courage to do it? However we cannot judge before we hear more, we can only be grateful that he escaped, when hardly anybody on the ship remained alive. We also heard that his friend Cube is lost. It was a terrible trial for Ducky, until she heard more details and never shall I forget how we spent yesterday…” (Mandache, p. 128-129)

[12] Grand Duke Serge Alexandrovich wrote to Grand Duchess Elizabeth: “I met with Kirill, who is back from Port Arthur. He is shattered and his spine badly damaged from a strike by a timber. He recounted the horrors.” (GARF, F. 648, op. 1, D. 41, l. 61.)

[13] Nicholas II met with Kirill twice on his return. Nicholas wrote in his diary: “April 26th. Monday. Quite a warm day. Walked for a long time in the morning. I had three reports - the last was Witte. We had breakfast: U[ncle]. Alexei and Kirill, who has just returned from P. Arthur after the death of the Petropavlovsk.

[14] At the second meeting, Kirill was unaware that on the previous day, his father Grand Duke Vladimir had asked for permission to send him abroad. While the Emperor was happy to make sure that Kirill would be cared for, he was clearly upset by the idea that any member of the Imperial Family would leave the country during a time of war. From Nicholas’ diaries: “April 30th. Friday. The weather improved, although it was raining in the morning while I was walking. After the report, received 19 petitions. Uncle Vladimir had breakfast with us. I had a conversation with him about Kirill - he insisted on the need for rest and treatment abroad! This made a heavy impression on me; to go abroad now!...” “May 1st. Saturday. The day turned out very fine. Had three reports before breakfast and two after. Kirill came for breakfast. We walked and rode on the pond. The plants are coming in nicely. Towards dinner we went to Gatchina, where I said goodbye to Mama before my trip to the south. We returned home at 10½ with Petya, the cat. traveled to Petersburg.” Kirill was clearly confused by the Emperor’s ambivalence on any number of topics, and for good reason.

[15] “Admiral Rozhdestvensky has the reputation of bien one of the most cool-headed and scientific naval officers in the Russian Service and the man of all others least likely to be blinded by panic or to lose his head in an emergency, however critical…” (Pall Mall Gazette, 27 December 1904, p. 7. The Pall Mall Gazette became the St. James Gazette in 1905.)

[16] This is an obfuscation on the part of Kirill Vladimirovich. Orthodox Canon Law states that all collateral blood relatives are prohibited to marry up until the seventh degree, that is, up until second cousins in any degree (i.e. once or twice removed). Canon 1091 specifically and additionally prohibits marriage between two first cousins; However, this is considered to be an impediment by ecclesiastical rather than divine law, and any diocesan bishop may grant a dispensation for them to marry validly in the Church. It is important to note that all that was needed was the Emperor’s permission. Under these stringent rules, a significant number of Romanov marriages would have been considered canonically invalid, including that of the Emperor Nicholas II himself (marrying his aunt’s sister), Grand Duchess Ksenia (marrying her first cousin once removed) and even the Dowager Empress (marrying the brother of her deceased fiancé).

[17] Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna to Queen Marie of Romania 11 October, 1905: “Dearest Missy! I can hardly believe it all, it seems like a dream and besides, this wedding was a very sympatique one after all. …. On Sunday I went first with Kyrill to the usual mass in the tiny church of Count Adlerberg, who, after he had once made up his mind, was very nice, attentive and even flattered, feeling very self-important. After mass, sister and the suite arrived there and we had tea, waiting until 12, to let Onchakoff arrive from Munich in the auto. He was late, so we began the wedding service without him but he came well in time to hold the crown over Kyrill's head… Ducky looked very handsome in a very becoming light grey dress and a yellow hat. She was calmly beaming, very touching to see ganz weihewoll [very somber] Kyrill was “calmly nervous” but also calmly pleased. He shows so little outward feeling, but one saw that he was émotionné.” (Mandache, p. 193)

Original Footnotes

(1939)

[i] 27 January, old style.

[ii] 28 January, old style.

[iii] Finance Minister.

[iv] Grand Duchess Elizabeth.

[v] The Terrible.

[vi] The Daring

[vii] Fearless.

[viii] Noiseless.

[ix] An excellent account of the voyage of the Baltic squadron and of the battle of Tsushima can be found in Frank Thiess' Tsushlma, 1937, Paul Zsolnay Verlag, Berlin, Wien, Leipzig.

[x] Alexander III.